Robert Louis Stevenson at the Abbey of Notre Dame des Neiges |

Father Michel, with his radiant face and rosy features, seemed to be a kind man of about thirty-five years. He led me to the office and served me a glass of liqueur to sustain me until dinner. We began a conversation, or rather I should say he listened to my chatter with a certain indulgence, though he seemed a bit absent, like a spirit in the presence of a flesh-and-blood creature. And, truth be told, when I recall that I was mostly talking about my appetite and that more than eighteen hours must have passed since Father Michel himself had taken a bite, I must admit he must have found something earthly in my words. Nevertheless, his politeness, though tinged with a certain spirituality, was absolutely exquisite, and I felt a deep desire to know more about Father Michel's past.

Father Michel, with his radiant face and rosy features, seemed to be a kind man of about thirty-five years. He led me to the office and served me a glass of liqueur to sustain me until dinner. We began a conversation, or rather I should say he listened to my chatter with a certain indulgence, though he seemed a bit absent, like a spirit in the presence of a flesh-and-blood creature. And, truth be told, when I recall that I was mostly talking about my appetite and that more than eighteen hours must have passed since Father Michel himself had taken a bite, I must admit he must have found something earthly in my words. Nevertheless, his politeness, though tinged with a certain spirituality, was absolutely exquisite, and I felt a deep desire to know more about Father Michel's past.

After being left alone in the convent garden for a while, I contemplated the main courtyard, which was nothing more than a space divided into sandy paths and flower beds of colorful dahlias, with a fountain in the center and a black statue of the Madonna. The buildings rose all around this place, sad and still lacking the patina of time and the elements. Nothing extraordinary apart from a turret and two gables topped with slates. Monks dressed in white and brown silently passed through the sandy paths, and when I first arrived, three hooded monks were kneeling on the terrace praying. A bald hill overlooked the convent on one side, and a forest loomed over it on the other. It was exposed to the winds. Snow fell intermittently from October to May, sometimes lingering for six weeks. But even if the buildings rose to the heavens in an atmosphere reminiscent of the skies, they still presented a stern and forbidding aspect from all sides.

After being left alone in the convent garden for a while, I contemplated the main courtyard, which was nothing more than a space divided into sandy paths and flower beds of colorful dahlias, with a fountain in the center and a black statue of the Madonna. The buildings rose all around this place, sad and still lacking the patina of time and the elements. Nothing extraordinary apart from a turret and two gables topped with slates. Monks dressed in white and brown silently passed through the sandy paths, and when I first arrived, three hooded monks were kneeling on the terrace praying. A bald hill overlooked the convent on one side, and a forest loomed over it on the other. It was exposed to the winds. Snow fell intermittently from October to May, sometimes lingering for six weeks. But even if the buildings rose to the heavens in an atmosphere reminiscent of the skies, they still presented a stern and forbidding aspect from all sides.

As for me, on that harsh September day, before being called to the table, I felt chilled to the bone. Once I had dined well, Brother Ambroise, an exuberant Frenchman (for those in charge of foreigners have permission to speak) took me to a cell reserved for retreatants. It was cleanly whitewashed and furnished with the bare essentials: a crucifix, a bust of the last pope, a French version of "The Imitation of Christ," a collection of pious meditations, and the life of Elizabeth Seton, a missionary apparently from North America, more specifically New England. As far as I know, there is still a vast field for evangelization in those regions. But do not forget Cotton Mather.

I would have liked to have him read this little book in heaven, where I hope he resides. However, he may already know it, and even better than I do. And undoubtedly, Mrs. Seton and he are the best of friends, joining their voices with joy in an endless psalmody. To complete the inventory of the cell, above the table was hung a summary of the rules for retreatants: what exercises they should follow, when to recite their rosary and meditate, when to rise and retire. Below, an important note stated: "Free time is spent in examination of conscience, confession, making good resolutions, etc." Making good resolutions, indeed... One could just as well talk about growing hair on one's head.

I would have liked to have him read this little book in heaven, where I hope he resides. However, he may already know it, and even better than I do. And undoubtedly, Mrs. Seton and he are the best of friends, joining their voices with joy in an endless psalmody. To complete the inventory of the cell, above the table was hung a summary of the rules for retreatants: what exercises they should follow, when to recite their rosary and meditate, when to rise and retire. Below, an important note stated: "Free time is spent in examination of conscience, confession, making good resolutions, etc." Making good resolutions, indeed... One could just as well talk about growing hair on one's head.

Barely had I explored my accommodation when Brother Ambroise reappeared. An English resident, it seemed, wished to speak with me. I protested my eagerness, and the religious introduced a sprightly little Irishman of about fifty years, a deacon in the church. He was dressed in strict canonical attire and wore on his head what, for lack of better knowledge, I can only qualify as an ecclesiastical cap. He had spent seven years as a chaplain in a convent of nuns in Belgium, then five years at Notre Dame des Neiges. He had never read an English newspaper, spoke only imperfect French, and even if he had spoken it like a native, he would not have had many opportunities for conversation where he resided. Moreover, he was a very sociable man, eager for news and with a childlike naiveté. While I was happy to have a guide to visit the monastery, he was equally delighted to see my British face and hear me speak English. He showed me the honors of his particular cell, where he spent his time among breviaries, Hebrew bibles, and Waverley novels. From there, he took me into the cloister, to the chapter house, led me through the vestiary where the brothers' robes and wide straw hats were hung, each with the name of a religious on a sign—names imbued with sweetness and originality, such as Basil, Hilarion, Raphael, or Pacificus.

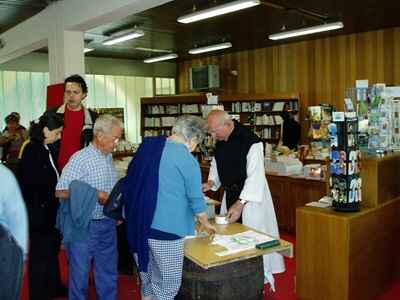

Finally, he took me to the library, where there were complete works of Veuillot and Chateaubriand, as well as the Odes and Ballads, if you please, and even Molière, not to mention the countless Fathers and a great variety of local and general historians. From there, my good Irishman took me on a tour of the workshops where the brothers do the baking, make cartwheels, and practice photography. One of them presides over a collection of curiosities, and another over a gallery of rabbits. For in a Trappist community, every monk has an occupation of his choosing outside of his religious duties and the general tasks of the establishment.

Finally, he took me to the library, where there were complete works of Veuillot and Chateaubriand, as well as the Odes and Ballads, if you please, and even Molière, not to mention the countless Fathers and a great variety of local and general historians. From there, my good Irishman took me on a tour of the workshops where the brothers do the baking, make cartwheels, and practice photography. One of them presides over a collection of curiosities, and another over a gallery of rabbits. For in a Trappist community, every monk has an occupation of his choosing outside of his religious duties and the general tasks of the establishment.

Each must sing in the choir if he has voice and ear, and join the reapers if he knows how to wield the scythe. But during his leisure, although he is far from idle, he can occupy himself according to his tastes. Thus, I was told, one brother was engaged in literature, while Father Apollinaire was busy building roads, and the Abbot employed himself in bookbinding. It was not long since this abbot had been installed, and on that occasion, by special favor, his mother was allowed to enter the chapel and attend the consecration ceremony. A proud day for her to have a mitred son! It is pleasant to think that she was allowed access to the cloister. In these comings and goings here and there, we crossed many fathers and brothers. Usually, they paid no more attention to our passage than to the flight of a cloud. But sometimes, the excellent deacon would allow himself to ask them a question, and he would be satisfied with a particular gesture of the hands, comparable to that of a dog swimming, or he would receive a refusal by the usual signs of negation. In either case, with lowered eyelids and a certain air of contrition, like someone who is very close to the devil himself.

The monks, with the exceptional permission of their Abbot, still took two meals a day. But it was already the time of their great fast, which begins around September and lasts until Easter. During this time, they eat only once every twenty-four hours, at two o'clock in the afternoon, twelve hours after they start their daily work and vigil. Their meals are not abundant, and even of these dishes, they take only sparingly. Although each monk is entitled to a small carafe of wine, many abstain from this treat. Certainly, most people overindulge these days; our meals serve not only to sustain us but also to provide a pleasant and normal distraction from the labors of life.

The monks, with the exceptional permission of their Abbot, still took two meals a day. But it was already the time of their great fast, which begins around September and lasts until Easter. During this time, they eat only once every twenty-four hours, at two o'clock in the afternoon, twelve hours after they start their daily work and vigil. Their meals are not abundant, and even of these dishes, they take only sparingly. Although each monk is entitled to a small carafe of wine, many abstain from this treat. Certainly, most people overindulge these days; our meals serve not only to sustain us but also to provide a pleasant and normal distraction from the labors of life.

Yet, even if excess is detrimental to health, I thought that the Trappist diet was sufficient. And I am amazed, when I reflect on it, at the freshness of their faces and their joy of living. I can hardly imagine people in better company and better health. In reality, on this austere plateau and with the incessant work of the monks, life is of uncertain duration, and death frequently visits Notre Dame des Neiges, at least that is what I was told. However, if they die without regret, they must also live without illness, for all seem to have firm flesh and a beautiful color. The only morbid sign I could notice was an abnormal brightness in their eyes, which rather seemed to reinforce the general impression of longevity and vitality.

Those I spoke with had a remarkably gentle nature, with a kind of healthy contentment of soul in their physiognomy and words. There was a warning to visitors, inviting them not to be offended by the few words of the monks, for it is in their nature to speak little. However, this warning could have been omitted. The guests were all overflowing with innocent conversations, and in my interactions with the community, it was easier to start a conversation than to end one. Except for Father Michel, who was a man of the world, they all showed genuine interest in any subject: politics, travel, my sleeping bag. And they seemed to take some pleasure in hearing the sound of their own voices.

Those I spoke with had a remarkably gentle nature, with a kind of healthy contentment of soul in their physiognomy and words. There was a warning to visitors, inviting them not to be offended by the few words of the monks, for it is in their nature to speak little. However, this warning could have been omitted. The guests were all overflowing with innocent conversations, and in my interactions with the community, it was easier to start a conversation than to end one. Except for Father Michel, who was a man of the world, they all showed genuine interest in any subject: politics, travel, my sleeping bag. And they seemed to take some pleasure in hearing the sound of their own voices.

As for those to whom silence is imposed, I can only admire how they endure their solemn and cold isolation. And yet, apart from the mortification perspective, it seems to me that I see a sort of policy, not only in the exclusion of women but even in this vow of silence. I have some experience of dead phalansteries of an artistic character, to say nothing of bacchanalian ones. I have seen several of these associations form easily and even more easily disappear. Under Cistercian rule, perhaps they could have lasted longer. In the presence of women, there are hardly any groups that can be formed among defenseless men.

The positive electrode is sure to prevail. Childhood dreams, adolescent plans are abandoned after a ten-minute encounter, and the arts and sciences and male professional bravado immediately yield to two tender eyes and a caressing voice. Moreover, after that, language is the greatest common divisor. I feel almost ashamed to continue this profane critique of a religious rule. However, there is still another point on which the order of Trappists calls for my testimony as a model of wisdom. Around two o'clock in the morning, the clapper strikes the bell, and so on, hour by hour, even sometimes every quarter of an hour, until eight o'clock, the moment of rest. Thus, in a meticulous manner, the day is divided between various occupations. The man who takes care of the rabbits, for example, rushes from his hutch to the chapel, to the chapter house, or to the refectory all day long. At any hour, he has an office to sing, a task to fulfill. From two o'clock when he rises in darkness until eight o'clock when he returns to receive the comforting gift of sleep, he remains standing, absorbed in multiple and changing tasks. I know many people, indeed several thousand a year, who do not have that luck in the schedule of their lives. In how many homes would the call of a monastery bell, breaking the days into easily undertaken portions, not bring peace of mind and the comforting activity of the body!

The positive electrode is sure to prevail. Childhood dreams, adolescent plans are abandoned after a ten-minute encounter, and the arts and sciences and male professional bravado immediately yield to two tender eyes and a caressing voice. Moreover, after that, language is the greatest common divisor. I feel almost ashamed to continue this profane critique of a religious rule. However, there is still another point on which the order of Trappists calls for my testimony as a model of wisdom. Around two o'clock in the morning, the clapper strikes the bell, and so on, hour by hour, even sometimes every quarter of an hour, until eight o'clock, the moment of rest. Thus, in a meticulous manner, the day is divided between various occupations. The man who takes care of the rabbits, for example, rushes from his hutch to the chapel, to the chapter house, or to the refectory all day long. At any hour, he has an office to sing, a task to fulfill. From two o'clock when he rises in darkness until eight o'clock when he returns to receive the comforting gift of sleep, he remains standing, absorbed in multiple and changing tasks. I know many people, indeed several thousand a year, who do not have that luck in the schedule of their lives. In how many homes would the call of a monastery bell, breaking the days into easily undertaken portions, not bring peace of mind and the comforting activity of the body!

We talk about fatigue, but real fatigue is not being a stupid dullard and letting life be poorly managed according to our narrow and foolish ways. From this perspective, we can certainly better understand the existence of the monks. A long novitiate and all proofs of spiritual constancy and physical vigor are required before one is accepted into the order. But I do not see that many postulants are discouraged by it.

We talk about fatigue, but real fatigue is not being a stupid dullard and letting life be poorly managed according to our narrow and foolish ways. From this perspective, we can certainly better understand the existence of the monks. A long novitiate and all proofs of spiritual constancy and physical vigor are required before one is accepted into the order. But I do not see that many postulants are discouraged by it.

In the photographic studio that so bizarrely stands among the buildings outside the cloister, my gaze was caught by the portrait of a young man in the uniform of a second-class infantryman. He was one of the monks who had completed his service, done marches and exercises, and stood guard during the required years in an Algerian garrison. Here is a man who had certainly considered both aspects of life before making a decision. Yet, as soon as he was released from military service, he returned to complete his novitiate.

This austere rule inscribes a man for heaven as a matter of right. When the Trappist is ill, he does not leave his habit. He rests on the deathbed as he has prayed and worked in his life of frugality and silence. And when the Liberator arrives, at the same moment, or even before he is carried away in his robe to lay the little that remains of him in the chapel among the endless plainchant, the peals of joyful bells, as if it were a wedding, soar from the slate tower and announce to the neighborhood that a soul has returned to God.

At night, under the guidance of my brave Irishman, I took my place in the choir to hear Compline and the Salve Regina by which the Cistercians end each of their days. There were none of those elements that strike the Protestant as puerile or spectacular in the liturgy of Roman Catholicism. A rigorous simplicity, sublimated by the surrounding romance, spoke directly to the heart. I recall the chapel whitened with lime, the hooded silhouettes in the choir, the lights alternately hidden or revealed, the rough manly chant, the ensuing silence, the sight of hoods inclined in prayer, and then the sharp click of the bell ceasing to indicate that the last office was finished and that the time for sleep had come. And when I remember this, I am not surprised to have escaped into the inner courtyard, in a sense seized by vertigo, and to have remained there, standing, like a madman, under the wind of the starry night. But I was tired, and when I had rested my mind with the memories of Elizabeth Seton, a dull work!

The cold and the croaking of the wind among the pines (for my room was on that side of the convent that adjoins the woods) quickly disposed me to sleep. I was awakened at midnight’s darkest hour, as it seemed, though it was actually two o'clock in the morning, by the first strikes of the bell. All the brothers then rushed to the chapel. The living dead, at this unusual minute, were already beginning the unrelieved labors of their day. The living dead! What a chilling image! And the words of a song from France came back to me that spoke the best of our paradoxical life:

What beautiful girls you have,

Giroflée,

Girofla!

What beautiful girls you have,

Love will count them!

And I thanked God for being free to wander, free to hope, free to love!

But there was another aspect of my stay at Notre Dame des Neiges. At this late season, the residents were few. However, I was not alone in the public part of the monastery. It is located near the entrance and includes a small dining room on the ground floor and, on the upper floor, a whole corridor of cells like mine. I foolishly forgot the pension price for a regular retreatant; it was between three and five francs per day, around the first price, I believe. Casual visitors like me could give what they wanted as a spontaneous offering; however, nothing was demanded from them.

But there was another aspect of my stay at Notre Dame des Neiges. At this late season, the residents were few. However, I was not alone in the public part of the monastery. It is located near the entrance and includes a small dining room on the ground floor and, on the upper floor, a whole corridor of cells like mine. I foolishly forgot the pension price for a regular retreatant; it was between three and five francs per day, around the first price, I believe. Casual visitors like me could give what they wanted as a spontaneous offering; however, nothing was demanded from them.

I must mention that when I was about to leave, Father Michel refused twenty francs as an excessive amount. I explained the reason that led me to offer him so much, but even then, out of a curious point of honor, he claimed not to accept this money himself. I do not have the right to refuse for the convent, he explained, but I would prefer that you give it to one of the brothers. I had dined alone, as I arrived late; however, at supper, I found two other guests. One was a parish priest from a rural church who had walked all morning from his parish near Mende to taste four days of retreat and prayer. He was a true grenadier with a blooming complexion and the circular wrinkles of a peasant.

And, while he lamented being hindered in his walk by his robe, I had a vivid imaginary portrait of him, making large strides, firm, of strong build, his cassock rolled up, across the bleak hills of Gévaudan. The other was a short, graying, stocky man, about forty-five to fifty years old, dressed in tweed and a sweater with the red ribbon of a decoration in his buttonhole. The latter was a character difficult to classify. He was an old soldier who had made his career in the army and had risen to the rank of captain. He retained something of the brusque decision-making style of the camps. On the other hand, as soon as his resignation was accepted, he came to Notre Dame des Neiges as a resident and, after a brief experience of the convent's rule, resolved to stay as a novice. Already, the new life was beginning to modify his physiognomy. He had already acquired a bit of the smiling and peaceful air of the brothers. However, he was neither an officer nor a Trappist: he partook of both states. And indeed, he was a man at an interesting turning point in life. Out of the tumult of cannons and trumpets, he was passing into this calm country bordering the grave where men sleep every night in their burial clothes and, like ghosts, communicate through signs.

And, while he lamented being hindered in his walk by his robe, I had a vivid imaginary portrait of him, making large strides, firm, of strong build, his cassock rolled up, across the bleak hills of Gévaudan. The other was a short, graying, stocky man, about forty-five to fifty years old, dressed in tweed and a sweater with the red ribbon of a decoration in his buttonhole. The latter was a character difficult to classify. He was an old soldier who had made his career in the army and had risen to the rank of captain. He retained something of the brusque decision-making style of the camps. On the other hand, as soon as his resignation was accepted, he came to Notre Dame des Neiges as a resident and, after a brief experience of the convent's rule, resolved to stay as a novice. Already, the new life was beginning to modify his physiognomy. He had already acquired a bit of the smiling and peaceful air of the brothers. However, he was neither an officer nor a Trappist: he partook of both states. And indeed, he was a man at an interesting turning point in life. Out of the tumult of cannons and trumpets, he was passing into this calm country bordering the grave where men sleep every night in their burial clothes and, like ghosts, communicate through signs.

At supper, we talked politics. I make it a point when I am in France to preach political goodwill and tolerance and to insist on the example of Poland, much like some alarmists in England cite the example of Carthage. The priest and the commander assured me of their sympathy regarding everything I said and sighed deeply about the harshness of contemporary political morals.

It is true, I said, that it is difficult to discuss with someone who does not absolutely profess the same opinions without immediately getting angry at you. Both declared that such a mindset was anti-Christian. While we were conversing in this manner, how did my tongue slip on a single word praising the moderation of Gambetta? The old soldier's face flushed with blood. With the palms of his two hands, he struck the table like an angry child.

What, sir! he exclaimed. How? Gambetta moderate! Would you dare justify these words?

But the priest had not forgotten the general spirit of our conversation. And suddenly, at the height of his anger, the old soldier met a warning glance fixed on his face. The absurdity of his conduct flashed before him, and the storm ended without him adding another word.

But the priest had not forgotten the general spirit of our conversation. And suddenly, at the height of his anger, the old soldier met a warning glance fixed on his face. The absurdity of his conduct flashed before him, and the storm ended without him adding another word.

It was only in the morning, after our coffee (Friday, September 27), that the couple discovered that I was a heretic. I suppose I had misled them with some admiring phrases about the monastic life around us. It was only by a direct question that the truth came to light. I had been welcomed with tolerance both by the naive Father Apollinaire and the shrewd Father Michel, and the good Irishman, when he learned of my religious frailty, simply patted me on the shoulder, saying, "You must become a Catholic and go to heaven!" But I now found myself in the midst of a different sect of orthodox individuals. These two men were bitter, unyielding, and narrow-minded like the worst Scots. And indeed, I would swear they were more puritanical.

The priest snorted loudly like a warhorse.

And you pretend to die in this kind of belief? he asked. There are no characters bold enough employed by mortal printers to translate his accent. Humbly, I observed that I had no intention of changing it. But he could not be satisfied with such a monstrous attitude. No! no! he exclaimed, you must convert. You have come here. God has led you here, and you must take advantage of the opportunity. I made a polite evasion. I appealed to my family affections, although I was addressing a priest and a soldier, two classes of citizens conveniently free from those amiable ties of home life. Your father and mother? exclaimed the priest, you will convert them in turn when you return home! I can almost see my father's head! I would rather seize the lion of Getulia in his lair than embark on such an enterprise against the theology of my own.

From now on, the hunt was on. Priest and soldier formed a relentless pack for my conversion. And the work of the Propagation of the Faith, for which the people of Cheylard had subscribed forty-seven francs ten centimes during the year 1877, continued valiantly against me its offensive. It was a baroque proselytism, but one of the most impressive. They never thought to convince me through an argument where I might attempt some defense. They held it certain that I was both ashamed and frightened of my position. They pressed me solely on the question of opportunity. "Now," they said, "now that God has led me to Notre Dame des Neiges, it is the predestined hour."

From now on, the hunt was on. Priest and soldier formed a relentless pack for my conversion. And the work of the Propagation of the Faith, for which the people of Cheylard had subscribed forty-seven francs ten centimes during the year 1877, continued valiantly against me its offensive. It was a baroque proselytism, but one of the most impressive. They never thought to convince me through an argument where I might attempt some defense. They held it certain that I was both ashamed and frightened of my position. They pressed me solely on the question of opportunity. "Now," they said, "now that God has led me to Notre Dame des Neiges, it is the predestined hour."

Do not be held back by self-love, the priest observed to encourage me.

For someone who professes feelings of all points equal towards all kinds of religion, and who has never been able, even for a minute, to seriously weigh the merits of this belief or that on the eternal level of beings, although there may be much to praise or blame on the temporal and secular level, the situation thus created was altogether unpleasant and painful. I made a second tactless mistake by attempting to argue that all returning ultimately leads to the same thing; we all tend to draw closer, through different paths, to the same Friend and Father without specifying. This, as it seems to secular minds, would be the only Gospel worthy of the name. But diverse men think differently. This revolutionary impulse made the priest raise all the terrors of the law. He launched into disturbing details about hell. The damned, he said on the faith of a little book he had read less than a week ago and which to add conviction to his conviction he had fully intended to carry with him in his pocket, the damned remain in the same position throughout eternity amid terrible tortures. And, while he discoursed thus, his physiognomy grew in nobility at the same time as in enthusiasm.

In conclusion, both agreed that I should seek to see the Prior, since Father Abbot was absent, and present my case to him without delay.

In conclusion, both agreed that I should seek to see the Prior, since Father Abbot was absent, and present my case to him without delay.

It is my advice as a former soldier, observed the commander, and that of Monsieur, as a priest. Yes, added the priest with a solemn nod, as a former soldier and as a priest. At that moment, while I was not without embarrassment on how to respond, one of the monks entered: a little brown fellow as lively as an eel, with an Italian accent, who immediately mixed into the discussion, but with a more conciliatory and persuasive mood, as befitted one of those amiable religious. You only had to look at him, he said. The rule was very hard. He would have liked to stay in his country, Italy; one knew how beautiful that country was, the beautiful Italy; but then, there were no Trappists in Italy, and he had a soul to save, and he was here.

I fear that, deep down in all these feelings, there was what a critic from India had gratified me with: "A hedonism that is dying." For this explanation of the brother's motives shocked me a bit. I would have preferred to think that he had chosen this existence for the interest it offered and not for ulterior motives. This shows how far I was from sympathizing with these good Trappists, even when I was doing my best to achieve it.

But to the priest, the argument seemed decisive. Listen to this! he exclaimed. And I have seen a marquis here, a marquis, a marquis—he repeated the sacred word three times in a row—and other high-ranking figures in society. And generals! And here, beside you, is this gentleman who has been under arms for so many years, decorated, an old warrior. And here he is, ready to devote himself to God. I was, during this harangue, so completely embarrassed that I pretended to have cold feet and made my escape from the room. It was a morning of fierce wind with a clear sky and long, powerful sunbeams. I wandered until dinner in a wild region to the east, cruelly struck and bitten by the tempest, but rewarded with picturesque views.

But to the priest, the argument seemed decisive. Listen to this! he exclaimed. And I have seen a marquis here, a marquis, a marquis—he repeated the sacred word three times in a row—and other high-ranking figures in society. And generals! And here, beside you, is this gentleman who has been under arms for so many years, decorated, an old warrior. And here he is, ready to devote himself to God. I was, during this harangue, so completely embarrassed that I pretended to have cold feet and made my escape from the room. It was a morning of fierce wind with a clear sky and long, powerful sunbeams. I wandered until dinner in a wild region to the east, cruelly struck and bitten by the tempest, but rewarded with picturesque views.

At dinner, the work of the Propagation of the Faith began again, and on this occasion, it was even more unpleasant for me. The priest asked me several questions about the despicable belief of my ancestors and received my replies with a sort of ecclesiastical sneer. Your sect, he said once, for I think you will agree that it would be giving it too much honor to call it a religion... As you wish, sir, I replied. You have the floor. In the end, he became angry at my resistance and although he was on his own ground and moreover, regarding this subject, an old man and thus had the right to indulgence, I could not help but protest against his lack of courtesy. He was sadly disconcerted. I assure you, he said, that I have no desire to laugh at the bottom of my heart. No other feeling drives me but the interest I have in your soul. And there ended my conversion. The brave man! He was not a dangerous phrase-maker but a country priest, full of zeal and faith. May he wander long in Gévaudan, his cassock rolled up, a solid man in his stride and solid in comforting his parishioners at the hour of death! I dare say he would bravely cross a snowstorm to go where his ministry would call him. It is not always the believer who is most overflowing with faith who makes the most skillful apostle! by Robert Louis Stevenson. From "Travels with a Donkey in the Cévennes"

Former holiday hotel with a garden along the Allier, L'Etoile Guest House is located in La Bastide-Puylaurent between Lozere, Ardeche, and the Cevennes in the mountains of Southern France. At the crossroads of GR®7, GR®70 Stevenson Path, GR®72, GR®700 Regordane Way, GR®470 Allier River springs and gorges, GRP® Cevenol, Ardechoise Mountains, Margeride. Numerous loop trails for hiking and one-day biking excursions. Ideal for a relaxing and hiking getaway.

Copyright©etoile.fr