In the Footsteps of the Muleskinners in La Bastide-Puylaurent |

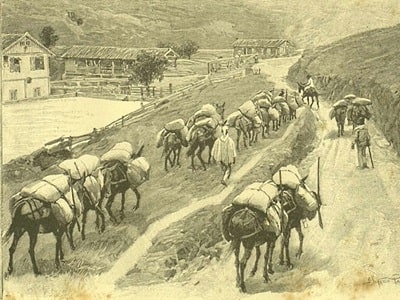

The Voie Regordane, which connected Saint-Gilles to La Bastide-Puylaurent, was an essential road in the Middle Ages, serving as a link between the south of France and the Central Massif. At the heart of this transport network, the muleskinners embodied the very essence of this commercial life.The muleskinners were men and women of the land, often from farming families. Their profession required in-depth knowledge of mules, those robust animals adapted to the mountains. The muleskinner had to know how to feed, care for, and load them in a balanced way. The mules, both sturdy and agile, could carry various goods: salt, wine, cereals, textiles... treasures from a time when each object had a story.

The Voie Regordane, which connected Saint-Gilles to La Bastide-Puylaurent, was an essential road in the Middle Ages, serving as a link between the south of France and the Central Massif. At the heart of this transport network, the muleskinners embodied the very essence of this commercial life.The muleskinners were men and women of the land, often from farming families. Their profession required in-depth knowledge of mules, those robust animals adapted to the mountains. The muleskinner had to know how to feed, care for, and load them in a balanced way. The mules, both sturdy and agile, could carry various goods: salt, wine, cereals, textiles... treasures from a time when each object had a story.

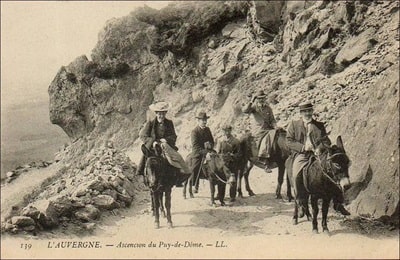

The Voie Regordane was more than just a simple path. It was surrounded by picturesque landscapes, with lush valleys and majestic mountains. That said, the road was also strewn with obstacles: steep slopes, narrow passages, sometimes scattered with unpleasant encounters. The muleskinner had to remain vigilant, not only in the face of natural dangers but also against thieves.

The Voie Regordane was more than just a simple path. It was surrounded by picturesque landscapes, with lush valleys and majestic mountains. That said, the road was also strewn with obstacles: steep slopes, narrow passages, sometimes scattered with unpleasant encounters. The muleskinner had to remain vigilant, not only in the face of natural dangers but also against thieves.

While traversing this path, they faced long and exhausting days. Often, the muleskinners would set off at dawn, hoping to reach a stop before nightfall. Each village represented a stop where they could meet, exchange news, and sometimes negotiate prices. These places were crucial for trade, but also for social life, as muleskinners forged strong bonds with the locals.

A life of help and solidarityIn this isolated region, the community of muleskinners was supportive. They helped each other with their travels, shared burdens around a fire, and told stories of their journeys. The evenings were an opportunity to laugh, sing, and spend time together, far from the wandering paths. These moments were crucial in a life where isolation could weigh heavily.

With the rise of the railway and modern roads in the 19th century, the role of the muleskinners gradually disappeared, leaving behind a rich heritage. Today, their stories resonate in the memories of older generations, and their courage is celebrated in local tales.The Voie Regordane, for its part, has become a popular hiking trail for nature and history lovers. By taking this path, hikers can still feel the spirit of the muleskinners, those hardworking individuals always in search of new horizons.

With the rise of the railway and modern roads in the 19th century, the role of the muleskinners gradually disappeared, leaving behind a rich heritage. Today, their stories resonate in the memories of older generations, and their courage is celebrated in local tales.The Voie Regordane, for its part, has become a popular hiking trail for nature and history lovers. By taking this path, hikers can still feel the spirit of the muleskinners, those hardworking individuals always in search of new horizons.

The picture that Mazon gave us of the muleskinners highlights the picturesque nature of these characters. Let us listen to him: "The muleskinner always wore a scarlet red wool hat, a hat that was customary to keep in any honorable company, even in church. On this hat sat a heavy and wide felt, whose broad edges were turned down like a parasol in sunshine, snow, or rain, and turned up in bicorne when it was necessary to go against the wind.This hat was sometimes adorned with a red cord with a tassel of the same color.

The muleskinners wore their hair tied back and only reluctantly let go of this venerable appendage at the very last moment. During the Restoration, everyone without exception still wore it, and many had retained it after 1830. Like the patrons of the Rhône, they had their ears adorned with large gold rings, with the difference that an anchor hung from these rings among the patrons, and a mule iron among the muleskinners.

The tie was red, and the vest was also red; bright colors were favored in the mountains. The jacket was that of prominent figures from the highlands, made of white cadis, with large copper buttons, quite roomy and tailored like a sailor's, finally presenting a remarkable similarity to the Breton jacket.

The tie was red, and the vest was also red; bright colors were favored in the mountains. The jacket was that of prominent figures from the highlands, made of white cadis, with large copper buttons, quite roomy and tailored like a sailor's, finally presenting a remarkable similarity to the Breton jacket.

The trousers, made of green cadis called "boutique," were short and tight. The gaiters, made of the same fabric but in white, were long, richly buttoned, and held at the knee with red garters adorned with a shining buckle.

The shoes were of Marlborough style, heavily ironed and each equipped with three leather ear tabs, serving as underfoot to secure the gaiters.

A belt made of the brightest red wool encircled the waist in a double or triple fold. Never was a commissioner from the Convention or the Paris Commune so splendidly girded in red as the most modest of Cevenol muleskinners.

Over this outfit, the muleskinners, in times of rain, snow, or cold, wore the coat of the mountain dwellers, vulgarly called the cape or limousine.

It is worth noting that this traditional costume, so full of colors, was not the only one, but Mazon seems to have described a fairly common type, at least at the end of the beautiful era of the muleskinners.

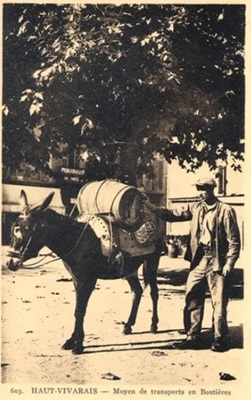

Even more picturesque must the mules appear, grouped into teams, the "coubles," which could sometimes exceed twenty-five heads. Each mule could carry wine in two bags, "boutes" if they were made from cowhide, "ouïres" if they were made from goat skin, with a capacity that could reach 70 to 80 liters each. Each beast was heavily and richly adorned.

Even more picturesque must the mules appear, grouped into teams, the "coubles," which could sometimes exceed twenty-five heads. Each mule could carry wine in two bags, "boutes" if they were made from cowhide, "ouïres" if they were made from goat skin, with a capacity that could reach 70 to 80 liters each. Each beast was heavily and richly adorned.

Let us listen to Mazon once more:

"Three round copper plates, about 15 cm in diameter, adorned the upper part of the head. One was placed on the forehead and the two others on the right and left, laying on the temples, all surrounded by red wool tassels floating in the intervals. These plates, called "glasses" in the vulgar and "phaleres" by antique dealers, produced the greatest effect, especially when the mule traversed under the rays of a burning sun; it was then a true display of brilliance and lightning..."

But the most beautiful ornament of the mule, at least the most visible, was the long and splendid red wool plume, a foot high, which rose between the two ears of the animal and completed its theatrical decoration.

These muleskinners are all or almost all "padgels," people of the mountains.

The main places of origin of the muleskinners: Luc, La Veyrune, La Bastide-Puylaurent, Les Huttes, St Laurent-les-Bains, La Garde-Guerin, Altier, Villefort, St Etienne-de-Lugdares, Loubaresse, Petit-Paris (near Montselgues)...

The main places of origin of the muleskinners: Luc, La Veyrune, La Bastide-Puylaurent, Les Huttes, St Laurent-les-Bains, La Garde-Guerin, Altier, Villefort, St Etienne-de-Lugdares, Loubaresse, Petit-Paris (near Montselgues)...

The mule is a hybrid resulting from the crossbreeding of a male donkey (a bardot) and a mare. It is known for its robustness, patience, and ability to work under difficult conditions. Mules have existed for thousands of years, and their domestication dates back to antiquity. They were particularly valued in the Egyptian and Roman civilizations. Thanks to their strength, endurance, and docile temperament, mules have been used as pack animals, serving to transport heavy loads over long distances, especially in mountainous regions and difficult terrain. In addition to their use as pack animals, mules have also been employed in agriculture to pull plows and carts.

Mules often have a robust body, strong limbs, and a head that blends the traits of the donkey and the mare. They generally have longer ears than horses but shorter than those of donkeys. Mules are known for their intelligence and sense of self-preservation. They are often more cautious and thoughtful than horses, which can be perceived as both stubbornness and wisdom. A notable aspect of the mule is that it is usually sterile due to the chromosomal difference between donkeys and horses. This means that mules cannot reproduce. Mules are reputed for their endurance and ability to carry heavy loads. They can work in extreme conditions without tiring as quickly as other working animals.

Mules often have a robust body, strong limbs, and a head that blends the traits of the donkey and the mare. They generally have longer ears than horses but shorter than those of donkeys. Mules are known for their intelligence and sense of self-preservation. They are often more cautious and thoughtful than horses, which can be perceived as both stubbornness and wisdom. A notable aspect of the mule is that it is usually sterile due to the chromosomal difference between donkeys and horses. This means that mules cannot reproduce. Mules are reputed for their endurance and ability to carry heavy loads. They can work in extreme conditions without tiring as quickly as other working animals.

La Bastide-Puylaurent was founded in the Middle Ages, around the 13th century. Bastidale municipalities often appear as places of commerce and exchange, serving as meeting points for local populations. The municipality is located at a high altitude, on the road connecting the Central Massif to the neighboring valleys, which favored trade. Its strategic location made it a stopping place for merchants and travelers.

Over the centuries, the economy of La Bastide-Puylaurent has relied on agriculture, livestock, and craftsmanship. The products from these activities, such as food and textiles, have been exchanged at local markets. The region is also known for its cheeses, particularly goat cheese, which has been able to find its place in local and regional trade. Fairs and markets have played an essential role in the commercial history of the municipality. These events allowed farmers and artisans to sell their products, exchange goods, and strengthen social ties. In the 19th century, the growth of transport networks, particularly with the development of the railway, contributed to dynamizing commerce by facilitating the transport of goods.

Former holiday hotel with a garden along the Allier, L'Etoile Guest House is located in La Bastide-Puylaurent between Lozere, Ardeche, and the Cevennes in the mountains of Southern France. At the crossroads of GR®7, GR®70 Stevenson Path, GR®72, GR®700 Regordane Way, GR®470 Allier River springs and gorges, GRP® Cevenol, Ardechoise Mountains, Margeride. Numerous loop trails for hiking and one-day biking excursions. Ideal for a relaxing and hiking getaway.

Copyright©etoile.fr