The History of the Cévennes |

Cévennes: Related to the Welsh "cefn," meaning "back," and to the Gaulish "Cebenna," a proper name for "the Cévennes": no certain equivalent outside of Celtic (LEBM, Etymological Lexicon of the most common terms in Modern Breton). Extensively, it means ridge, back, keel (of a boat). (An older form is kefn/kevn – Dict. celto-bret. Le Gonideg, 1850). The name is probably Ligurian "Cemmenon" or "Cibenon." Strabo writes this name in the singular as "kèmmènon," Ptolemy in the plural as "kèmènna." Avienus writes "Cimenici regio." The Gauls substituted the Ligurian term, which was meaningless to them, with the name "Cebenna," meaning back (in Welsh "cefn," "cefyn"; also used in Wales to designate mountains). Pliny writes "Cebenna," and Caesar "Cevennna." (H. d'Arbois de Jubainville). Welsh "cefn," back. Etymology: Welsh < Brittonic (Welsh < Brittonic) *KEMN- = escaena (back, ridge). Related forms: Breton kein = escaena. (Dict. gall.-catalan).

***

The discovery of a part of a skull of a man, embedded in sands and lapilli from the Pleistocene volcano of Denise near Le Puy-en-Velay, proved that man witnessed the last Quaternary eruptions.

The discovery of a part of a skull of a man, embedded in sands and lapilli from the Pleistocene volcano of Denise near Le Puy-en-Velay, proved that man witnessed the last Quaternary eruptions.

Man, to defend himself against the formidable animals of this period, armed his arm with spears, sharp stones (knuckle-dusters), and finally arrows that struck fatally from a distance. For this, the flint that he knew how to shape by chipping was of primary utility. The terrains he encountered in the Cévennes contained little flint, but the terrains of Aveyron had it in abundance, and the Cretaceous deposits on the left bank of the Rhône offered it plentifully. It is likely that there was an early movement of transhumance by tribes of fishermen and hunters between the banks of the Rhône or the coastal areas and the high Cévennes plateaus, where it is evident they could abundantly supply the necessary flint. In the Neolithic period, when man had learned to finely shape and polish stones, he used the hard materials he found, especially in the volcanic region, such as basalt, quartz, jadeite, fibrolite (aluminosilicate), actinolite, etc.

The large number of caves and rock shelters he found in the limestone of Ardèche, the country of Gras, the causses of Saint-Remèze, etc., in Lozère, the Cévennes, the Causse Noir, the Méjean causses, Sauveterre, Séverac, and Larzac, allowed prehistoric man to multiply there. Thus, there are numerous megalithic monuments he left behind; Aveyron possesses the tenth of the classified dolmens in France. The menhirs or standing stones are also very numerous: the menhir was a stone of primary utility, and its sacred character ensured its preservation. One must have wandered over these immense plateaus, whether in foggy weather or during the famous snowstorms called "Siberian," to realize the necessity of these landmarks for all, shepherds, transhumants, and traders of flint.

The large number of caves and rock shelters he found in the limestone of Ardèche, the country of Gras, the causses of Saint-Remèze, etc., in Lozère, the Cévennes, the Causse Noir, the Méjean causses, Sauveterre, Séverac, and Larzac, allowed prehistoric man to multiply there. Thus, there are numerous megalithic monuments he left behind; Aveyron possesses the tenth of the classified dolmens in France. The menhirs or standing stones are also very numerous: the menhir was a stone of primary utility, and its sacred character ensured its preservation. One must have wandered over these immense plateaus, whether in foggy weather or during the famous snowstorms called "Siberian," to realize the necessity of these landmarks for all, shepherds, transhumants, and traders of flint.

In Haute-Loire, Velay has revealed, apart from the finding at Denise, no traces of the Paleolithic period or chipped stone; the Neolithic period or polished stone is not better represented there. Velay, enclosed by high mountains and large volcanic plateaus, communicating only through narrow gorges with the Loire or Allier, and not at all with the Lower Rhône, seems to have been outside the seasonal explorations mentioned above. Only eight dolmens are reported there: among these, one must mention the one that was at the summit of Mont-Anis and dominated the station where Le Puy-en-Velay was established. Its sacred character survived the religions of prehistory and the Druids; it became the stone of the lepers, the stone of fevers, and remains the object of a continued pilgrimage.

The Bronze Age at least led to some fortunate discoveries: the museum of Le Puy-en-Velay has preserved most of the objects collected at Saint-Pierre-Ainac, at 850 m. altitude and 13 km east of Le Puy-en-Velay, a peddler's trinket consisting of 78 objects, new for sale or broken for melting; the museum of Lyon acquired a small treasure of gold jewelry from the Montée des Capucins in Le Puy-en-Velay. From the Iron Age, very little has been found in Haute-Loire, despite Aymard's research.

The Bronze Age at least led to some fortunate discoveries: the museum of Le Puy-en-Velay has preserved most of the objects collected at Saint-Pierre-Ainac, at 850 m. altitude and 13 km east of Le Puy-en-Velay, a peddler's trinket consisting of 78 objects, new for sale or broken for melting; the museum of Lyon acquired a small treasure of gold jewelry from the Montée des Capucins in Le Puy-en-Velay. From the Iron Age, very little has been found in Haute-Loire, despite Aymard's research.

Lozère, open towards the valley of the Lot, in the southwest, like the Dordogne, was clearly inhabited since the Paleolithic period, but did not yield many finds from this era. However, a flint working workshop was active at Saint-Léger-de-Malzieu, an excellent deposit of lake-origin flint. Conversely, the Neolithic period has finely shaped axes and spear points, simulacra of axes for tombs in jadeite, necklaces in jet, bone needles, pottery (not turned), and the remains of a whole type of civilization. Prehistory in Lozère has led to significant work by Abbé Delaunay, Abbé Solanet, Malafosse, Dr. Prunières especially, and Marcellin Boule. It was on the occasion of a finding made in 1873 that Dr. Prunières, supported by Dr. Broca, revealed the existence of prehistoric trepanation on intentionally perforated skulls, where the work of the healing bumps is clearly visible.

The museum of the Agricultural Society in Mende contains a treasure from the Bronze Age found at Carnac, near La Malène, on the Méjean causse: arrowheads, vases, buttons, bracelets, rings, etc.

The museum of the Agricultural Society in Mende contains a treasure from the Bronze Age found at Carnac, near La Malène, on the Méjean causse: arrowheads, vases, buttons, bracelets, rings, etc.

It should be noted that the dolmens and tumuli of the Causses continued to receive burials until the end of the Merovingian period; coins from the bishops of Mende from the 12th century have been found there, so great was the permanence of traditional life on the causse.

The prehistoric stations and caves of the Gard department (stations of Collorgues, Fontbouisse; cache of Vers; caves of Meyrannes, Sartanette cave, caves of Gardon, etc.) have provided particularly interesting prehistoric documents to the archaeological museum and the museum of Nîmes.

The oppidum of Murviel-lès-Montpellier, that of Nages, near Nîmes, the caves of Bize, and the dolmen of Villeneuye-Minervois are, outside of the Rhône valley, the main prehistoric curiosities of Lower Languedoc; we must add the collections of the archaeological society museum of Montpellier and those of the museum of Narbonne, partly composed of objects found in the vicinity of these cities.

The Tarn department has provided few prehistoric monuments or objects.

At the dawn of the historical period, the entire Southeast of France is inhabited by the Ligurians. They created what has been called the civilization of the oppida, common to the region we are discussing and Provence. This civilization replaced that of the caves but directly derived from it.

What are, indeed, from the point of view of human activity, the characteristics of the French Mediterranean south? It is to encompass two major routes of exceptional importance: one oriented from East to West, which, through the valleys of Argens and Arc, then through the plain of Lower Languedoc, the valley of Aude, and those of Hers and Garonne, leads from Italy to the Atlantic with an easy bifurcation towards Spain; the other, oriented from South to North, the valley of the Rhône, which leads directly to the North Sea.

What are, indeed, from the point of view of human activity, the characteristics of the French Mediterranean south? It is to encompass two major routes of exceptional importance: one oriented from East to West, which, through the valleys of Argens and Arc, then through the plain of Lower Languedoc, the valley of Aude, and those of Hers and Garonne, leads from Italy to the Atlantic with an easy bifurcation towards Spain; the other, oriented from South to North, the valley of the Rhône, which leads directly to the North Sea.

The first brought bronze, the second brought amber. But also, these two great passages are bordered by steep mountains where strong positions abound from which one can safely monitor the plains. Finally, it is the inevitable importance of economic exchanges between the mountain and the plain.

The oppida, knots of roads and centers of cultivated zones, thus marked an undeniable progress over the age of caves, but this progress was further accentuated by the relationships that the inhabitants, taking direct contact with Hellenistic civilization, maintained with the trading posts that the Phoenicians in the 8th century and then in the 6th century the Phocaeans established on the coast (Marseille, La Rouanesse near Beaucaire, Agde).It is likely that in the middle of the 4th century, the Celts or Gauls invaded the region, militarily occupying the oppida in order to dominate the autochthonous population, probably more numerous than they were. However, a fusion seems to have occurred quite quickly, and, in the absence of other testimonies, the curious Gallic coins would suffice to show how easily the rough conquerors underwent the civilizing influence of Greek merchants.

The year 218 saw one of the most famous events in history take place in the region we are discussing, whose repercussions would be considerable: Hannibal's expedition. The Carthaginian army, although it generally managed to gain the benevolent neutrality of the Gauls, still had to contest the crossing of the Rhône with the Volci, and then, neglecting the troops that the Romans had disembarked in Marseille, plunged into the Alps to cross them. It is known how the conflict between Rome and Carthage ended. One of its consequences was the Roman conquest of Spain, and this conquest, in turn, had the fatal consequence of the occupation of the Gallic coast. Despite the relative ease of maritime communications, the victors soon thought of using and improving the road that the Punic invaders had taken. They took advantage of the weakness of their Marseille allies, unable to defend themselves against the aggressions of the Celto-Ligurians, to come to their aid and methodically occupy the country: Nice in 154, Aix in 123, Nîmes in 120, Narbonne in 118, Toulouse in 106.

The route followed by Hannibal became a Roman road, the Domitian Way, and the conquered region became Gallia Transalpina and, a little later, Provincia Romana, a military government that Provence retains the name. The Romans, indeed, had to occupy the hinterland to protect the Domitian Way from raids, and it is very interesting to note that the part of the Provincia located on the right bank of the Rhône almost had the same boundaries as our 18th-century Languedoc: it indeed encompassed the Helvii (Vivarais), the Volci Arecomici (Lower Languedoc), and the Volci Tectosages (Toulousain and Albigeois). The land of the Ruteni (Rouergue) remains outside the Province, just as at the end of the 18th century, it belonged to the government of Guyenne and to the intendancy of Montauban, forming a large salient that extends into the heart of Languedoc. However, the land of the Vellaves (Velay) and that of the Gabales (Gévaudan) remain outside the Roman Province.

The route followed by Hannibal became a Roman road, the Domitian Way, and the conquered region became Gallia Transalpina and, a little later, Provincia Romana, a military government that Provence retains the name. The Romans, indeed, had to occupy the hinterland to protect the Domitian Way from raids, and it is very interesting to note that the part of the Provincia located on the right bank of the Rhône almost had the same boundaries as our 18th-century Languedoc: it indeed encompassed the Helvii (Vivarais), the Volci Arecomici (Lower Languedoc), and the Volci Tectosages (Toulousain and Albigeois). The land of the Ruteni (Rouergue) remains outside the Province, just as at the end of the 18th century, it belonged to the government of Guyenne and to the intendancy of Montauban, forming a large salient that extends into the heart of Languedoc. However, the land of the Vellaves (Velay) and that of the Gabales (Gévaudan) remain outside the Roman Province.

This will naturally be the base of Caesar's operations for the conquest of Gaul, and it is he who first mentions mons Cevenna, which he made his troops cross, despite the snow, in February 52, from the coastal stationed troops, a simple maneuver intended to mask the arrival in Auvergne, from the North, of the ten legions he had concentrated in the region of Langres: it was the beginning of the campaign that would mark the siege of Avaricum and the failed attack on Gergovie.

After the conquest, the Roman Province became Narbonnaise, a proconsular province. It was administered with that respect for local traditions, that meticulous accuracy that was everywhere the mark of Roman genius. In the old Celto-Ligurian towns, colonies of veterans or Roman citizens formed the framework of a wholly peaceful occupation, as the indigenous population easily accepted the victors. At the end of the 4th century, the Narbonnaise Première, detached from the great Narbonnaise, closely resembles our Languedoc. Narbonne prevailed over Nîmes, Béziers, and even Toulouse. The wines of Biterrois are already renowned.

After the conquest, the Roman Province became Narbonnaise, a proconsular province. It was administered with that respect for local traditions, that meticulous accuracy that was everywhere the mark of Roman genius. In the old Celto-Ligurian towns, colonies of veterans or Roman citizens formed the framework of a wholly peaceful occupation, as the indigenous population easily accepted the victors. At the end of the 4th century, the Narbonnaise Première, detached from the great Narbonnaise, closely resembles our Languedoc. Narbonne prevailed over Nîmes, Béziers, and even Toulouse. The wines of Biterrois are already renowned.

The Romanization of this region, already touched by Hellenism, was so profound that it had two curious consequences: the first is that even today, the population speaks nothing but a transformed vulgar Latin; the second is that Christianity progressed there less rapidly than on the banks of the Saône, Loire, or Seine; it would not truly organize itself until the second half of the 4th century, and it is permissible to say that, through the centuries, the Languedocian genius, however marked by Christianity, remained even more Roman.

The great invasions were marked by the settlement, in 419, with the consent of Emperor Honorius, of the Visigoths in Aquitaine (Nantes, Bordeaux, Toulouse). In the middle of the 5th century, they occupied the rest of Narbonnaise. These barbarians, who had been for some time already in the service of the Empire, did not destroy the Gallo-Roman civilization but utilized it as best as possible, so that the region did not provide "Visigoth" monuments, except for burial sites and jewelry. Fustel de Coulanges has also shown that the invaders must have been far fewer than the Gallo-Romans; they were only somewhat rough garrison troops.

The end of the 5th century marked the peak of the Visigoth kingdom, which then extended from Orleans to the columns of Hercules, encompassing almost all of Spain. The victory won by Clovis at Veuille in 507 drove the Visigoths from the Southwest of France, who managed to retain the old Narbonnaise minus the district of Toulouse. This region, a province of the Visigoth kingdom of Spain, then took the name of Septimanie or Gothia.

The end of the 5th century marked the peak of the Visigoth kingdom, which then extended from Orleans to the columns of Hercules, encompassing almost all of Spain. The victory won by Clovis at Veuille in 507 drove the Visigoths from the Southwest of France, who managed to retain the old Narbonnaise minus the district of Toulouse. This region, a province of the Visigoth kingdom of Spain, then took the name of Septimanie or Gothia.

The 8th century saw the appearance of the Saracens. It is now demonstrated that these new invaders acted as mere plunderers, unable to create anything, and that the region has not retained any "Arab antiquity." The extraordinarily vivid memory of the "Moors" or "Saracens," both here and in Provence, likely stems from the fact that, for five centuries, the crusade was constantly preached for the deliverance of Spain and that, well before the great expeditions to the Holy Land, many French from the South had, in small groups, crossed the Pyrenees to fight the Infidels.

In any case, it was through Narbonne that, in 719, the Arabs began the adventurous expedition which Charles Martel put an end to at Poitiers in 732. However, they managed to keep Septimania until 760, when they were expelled by Pepin the Short.

Under the Merovingians and Carolingians, Toulouse remained the capital of Aquitaine and changed masters according to the divisions that ruined these two dynasties. Charlemagne had retained Septimania as an administrative division of his Empire, a "march" whose role was to strengthen the Spanish march, the future county of Barcelona.

In the anarchy that followed the disintegration of Charlemagne's Empire, the counts of Toulouse, simple officials, depending on the emperor, king, or duke of Aquitaine, became hereditary counts, and the county of Toulouse, detached from the duchy of Aquitaine, became, from the beginning of the Capetian dynasty, one of the great fiefs directly moving from the Crown. However, the king was far away, and his sovereignty was purely theoretical.

During the 11th and 12th centuries, the dynasty of the counts of Toulouse continued to grow. Without going into the details of this complex history, it is enough to say that at the dawn of the 13th century, the count of Toulouse possessed Toulouse, Agenais, Quercy, and Rouergue, that he was duke of Narbonne (former Septimania) and marquis of Provence (Comtat Venaissin and Valentinois), and that he had as vassals the counts or viscounts of Foix, Astarac, Armagnac, Pardiac, Lomagne, Razès, Albi, Carcassonne, Narbonne, Béziers, and Nîmes. It is clear how this domain differed from the future province of Languedoc; it strongly encroached on Gascony, but it lacked the ecclesiastical counties of Viviers, Velay, and Gévaudan.

During the 11th and 12th centuries, the dynasty of the counts of Toulouse continued to grow. Without going into the details of this complex history, it is enough to say that at the dawn of the 13th century, the count of Toulouse possessed Toulouse, Agenais, Quercy, and Rouergue, that he was duke of Narbonne (former Septimania) and marquis of Provence (Comtat Venaissin and Valentinois), and that he had as vassals the counts or viscounts of Foix, Astarac, Armagnac, Pardiac, Lomagne, Razès, Albi, Carcassonne, Narbonne, Béziers, and Nîmes. It is clear how this domain differed from the future province of Languedoc; it strongly encroached on Gascony, but it lacked the ecclesiastical counties of Viviers, Velay, and Gévaudan.

Protected by enlightened princes, inheritor of Gallo-Roman civilization, maintaining relations with the East through the port that Montpellier had at the mouth of the Lez, relations that the crusades had developed, the population of the county of Toulouse was, at least in literature and manners, well ahead of the North of France. Christian convictions, attraction to the East, a taste for adventure, ambition? We will never know the complexity of the reasons that led Count Raymond IV to take the cross and die, in 1105, as Count of Tripoli.

Toulousain civilization is characterized by the frequency of small private property, by the small number of serfs, especially in the plain, by the use of "written law" of Roman origin, by the grouping of the population in towns and large villages, the latter generally having succeeded a Gallo-Roman villa. Hence the early power of the "communes," which, from the 12th century onwards, were directed by consuls or capitouls and enjoyed genuine administrative autonomy and, to some extent, political autonomy. It is here, through the continuous rise of a bourgeoisie that lent money to spendthrift lords that it had earned through trade and thus made them its debtors, that Languedoc, like Provence, resembles Italy much more than Northern France.

In contrast to Northern France, Toulouse civilization is secular. The Church, however, played its role here as elsewhere; in the chaos of the early Middle Ages, it was the only framework of the country, it maintained as much as it could of Greco-Latin culture, organized charity, created "free towns," and facilitated the reduction of serfdom. But it is a fact that the Meridionals, at least those from the plain, who have number and wealth on their side, do not provide the Church with theologians or mystics; as in Provence, the weakness of Benedictine monasticism is striking, and one must also consider the role of Northern men in the foundations that arise from it.

In contrast to Northern France, Toulouse civilization is secular. The Church, however, played its role here as elsewhere; in the chaos of the early Middle Ages, it was the only framework of the country, it maintained as much as it could of Greco-Latin culture, organized charity, created "free towns," and facilitated the reduction of serfdom. But it is a fact that the Meridionals, at least those from the plain, who have number and wealth on their side, do not provide the Church with theologians or mystics; as in Provence, the weakness of Benedictine monasticism is striking, and one must also consider the role of Northern men in the foundations that arise from it.

Caught up in the worldly life of the cities where they reside, the bishops, who generally belong to the nobility of the county, are influenced negatively by it, and the same can be said for the priests who, in the absence of a genuine peasantry, must be recruited from the people of the communes. Hence the relaxation of doctrine and morals, a tolerance regarding faith that, at this time, can only be explained by an unusual indifference. Even during the crusade, the Northerners noted the bravery and brilliance of the Meridionals, but also their levity and skepticism.

On the other hand, well before the regular establishment of the universities of Toulouse and Montpellier, studies were flourishing, especially law and medicine, followed by letters. As in Bologna or Salerno, teaching owes a lot to the Arabs and Jews.

We will see later that the religious architecture of the country has close ties with that of Lombardy and Catalonia and has also produced some great monuments and a school of sculpture that is distinctly Languedocian, but nothing will be more original than the literature of the troubadours for its art, its technique, the subtlety of the expressed sentiments, and the prominent place it gives to women. This poetry contributed to the softening of manners, to the enrichment of sensitivity, and in the 13th century, while it will fade in its country of origin, it will carry, along with the prodigious architecture of Île-de-France and Burgundy, the mark of French genius to Italy and Germany.

The kings of France, who had just undergone a harsh experience with the dukes of Normandy and the counts of Anjou, could not allow such a peril to reconstitute itself in the South, where the counts of Toulouse might settle in Spain as the Plantagenets had done in England, and France was once again dismembered. Philip Augustus, that great king who had just reclaimed Normandy and Anjou, took advantage of an extraordinary opportunity to intervene.

The kings of France, who had just undergone a harsh experience with the dukes of Normandy and the counts of Anjou, could not allow such a peril to reconstitute itself in the South, where the counts of Toulouse might settle in Spain as the Plantagenets had done in England, and France was once again dismembered. Philip Augustus, that great king who had just reclaimed Normandy and Anjou, took advantage of an extraordinary opportunity to intervene.

The states of the count of Toulouse were filled with heretics whom history has called Cathars, and also Albigensians because they were particularly numerous around this city. This heresy was a mix of Arianism and Manichaeism brought by the Visigoths and maintained by merchants who came from Eastern Europe, of Judaism brought by the numerous Jews who lived peacefully in the region where they had flourishing schools, and even of Islam left by the Arabs. The extreme laxity of southern manners made heresy benefit from astonishing tolerance. Practically, the Cathars, under the pretext of repudiating the corruption of a highly hierarchical society, tended towards a sort of communism. Freeing the spirit from the grip of matter was their main concern; to achieve this, they advocated chastity, restricted nourishment to the point of starvation, and, logically, they advised libertinism and abortion for those who did not feel capable of leading the pure life of the "perfect." From Christ's famous words about the sword, they concluded that society has neither the right to punish nor to make war. They were, in short, what we would today call anarchists and conscientious objectors.

The papacy initially tried to convert them through preaching. It was in vain, and in 1208, the assassination of the legate prompted Innocent III to preach the crusade. As in all these enterprises, material considerations mingled with religious reasons. If the southern nobility saw in the weakening of Catholicism an opportunity to seize the Church's property, the northern nobility saw in the crusade an opportunity to take hold of the goods of the heretical lords, and if part of the people was attached to heresy, there was another part, the shopkeepers, for example, who saw their businesses deteriorating as churches, abbeys, and pilgrimages were neglected. Thus, the southern nobility in favor of heresy, which provided the necessary military frameworks for resistance, found themselves engaged in a relentless struggle. Cautiously, the king of France was content to authorize a small number of lords – although the number exceeded – to participate in the crusade.

The papacy initially tried to convert them through preaching. It was in vain, and in 1208, the assassination of the legate prompted Innocent III to preach the crusade. As in all these enterprises, material considerations mingled with religious reasons. If the southern nobility saw in the weakening of Catholicism an opportunity to seize the Church's property, the northern nobility saw in the crusade an opportunity to take hold of the goods of the heretical lords, and if part of the people was attached to heresy, there was another part, the shopkeepers, for example, who saw their businesses deteriorating as churches, abbeys, and pilgrimages were neglected. Thus, the southern nobility in favor of heresy, which provided the necessary military frameworks for resistance, found themselves engaged in a relentless struggle. Cautiously, the king of France was content to authorize a small number of lords – although the number exceeded – to participate in the crusade.

Fifty thousand Northerners led by the abbot of Cîteaux, Arnaud Amalric, rushed to the South. After the capture of Béziers and Carcassonne, whose inhabitants were massacred (1209), Simon de Montfort (Montfort-l'Amaury near Paris), an insensitive yet devout man, but honest, intelligent, a warrior and remarkable administrator, took command of the methodical disarmament operations of the country through flying columns and the eviction of the compromised local lords. Until then, the count of Toulouse, Raymond VI, very indecisive, without firmly established convictions, had let things unfold.

However, the methods of the crusaders, who behaved as foreigners in a conquered land (they were merely following papal instructions), gained unanimous support from his Catholic or heretical subjects. He took up arms and, genuinely raising the banner of independence for the Occitan-speaking lands against the "Barbarians" from the North, he called for help from the king of Aragon, his brother-in-law. What was once a religious struggle was becoming political. The two princes were defeated by Simon de Montfort at Muret, at the gates of Toulouse, on September 12, 1213, and the king of Aragon died bravely in battle. Thus, hopes that were undoubtedly chimerical were shattered, but some Languedocians still lament the consequences of that disastrous day.

However, the methods of the crusaders, who behaved as foreigners in a conquered land (they were merely following papal instructions), gained unanimous support from his Catholic or heretical subjects. He took up arms and, genuinely raising the banner of independence for the Occitan-speaking lands against the "Barbarians" from the North, he called for help from the king of Aragon, his brother-in-law. What was once a religious struggle was becoming political. The two princes were defeated by Simon de Montfort at Muret, at the gates of Toulouse, on September 12, 1213, and the king of Aragon died bravely in battle. Thus, hopes that were undoubtedly chimerical were shattered, but some Languedocians still lament the consequences of that disastrous day.

In any case, the power of Toulouse was ruined, and let us note that the king of France was not responsible as a suzerain. It was not a royal army but a crusading army that had laid the country to waste. The monarchy reserved itself.

In 1215, the year of Bouvines and the Great Charter, the heir to the Crown, the future Louis VIII, occupied Toulouse while the pope dispossessed Raymond of his estates. He took up arms again in 1217 and reoccupied Toulouse, where the "French" were massacred. Montfort laid siege to the city, but on June 25, 1218, a projectile struck him in the head, and the siege was lifted. During his three-year reign (1223-1226), Louis VIII, eager to reap the fruits of paternal policy, took up the cross against the Albigensians under conditions more favorable to France than to the papacy. He would die during the expedition, but the county was reoccupied. Finally, after various alternations, Raymond VII, son of Raymond VI, renounced the struggle and, by the Treaty of Meaux (1229), the work of Blanche of Castile, retained only part of his domains on the condition of marrying his daughter to Alphonse of Poitiers, brother of Louis IX, it being understood that upon the death of Raymond VII, which occurred in 1249, Alphonse of Poitiers would become count of Toulouse, and if he died without children, the county would revert to the Crown, which occurred in 1271.

Since then, Languedoc, which would never be granted as an apanage, would be administered directly by royal officials. The firm yet benevolent policy of Louis IX and his brother soon repaired the ruins caused by the crusade, and the inhabitants of the county became, it must be proclaimed, unconditional French. The repression of Albigensianism, an ungrateful and sometimes odious task, was the work of the Inquisition.

Since then, Languedoc, which would never be granted as an apanage, would be administered directly by royal officials. The firm yet benevolent policy of Louis IX and his brother soon repaired the ruins caused by the crusade, and the inhabitants of the county became, it must be proclaimed, unconditional French. The repression of Albigensianism, an ungrateful and sometimes odious task, was the work of the Inquisition.

As early as 1207, the future St. Dominic had organized the fight against heresy. It was in Toulouse that, in 1215, he founded the Order of Preachers to suppress it and that, in 1229, a council gathering the bishops of the South instituted the tribunal of the Inquisition, whose excesses the King's men tried at every moment to repress, nearly reigniting the war several times. But the rigors of the famous tribunal, which lasted until the middle of the 14th century and effectively extirpated the last remnants of heresy, seem to have left indelible memories and transformed the character of the inhabitants who, from being tolerant and indifferent, became formidable fanatics, as the course of their history will show.

The assimilation was primarily the work of Philip the Fair. In a curious turn of events, it was Languedoc that provided him with the legal experts he would use in his struggle against the papacy. Beaucaire and Nîmes developed, the king of France took hold of Montpellier, which the Treaty of Meaux had left to the king of Aragon, and in the absence of Marseille, he took full advantage of Aigues-Mortes as a port. The 13th century also saw the foundation of the Universities of Toulouse (1229) and Montpellier (1289).

The territory of Languedoc was still to undergo changes. By the Treaty of Amiens (1279), Agenais and Armagnac came under the influence of the duchy of Guyenne, which the king of England held as a fief of the king of France. On the other hand, following the acquisition of Lyon, Philip the Fair, in 1307, made contracts with the bishops of Puy-en-Velay, Mende, and Viviers, which practically united Velay, Gévaudan, and Vivarais with the Crown. The occupation of this last region gave France almost the entire right bank of the Rhône. Philip the Fair had a bridgehead built at Villeneuve in front of Avignon, and Philip of Valois had another built at Sainte-Colombe in front of Vienne. The same king completed, in 1349, the acquisition of Montpellier. Finally, as a consequence of the unfortunate Treaty of Brétigny (1360), Rouergue was ceded to the king of England, and although Charles V reconquered it ten years later, it would henceforth follow the administrative destinies of Guyenne. The boundaries of Languedoc would not change again until the destruction of the province during the Revolution.

The territory of Languedoc was still to undergo changes. By the Treaty of Amiens (1279), Agenais and Armagnac came under the influence of the duchy of Guyenne, which the king of England held as a fief of the king of France. On the other hand, following the acquisition of Lyon, Philip the Fair, in 1307, made contracts with the bishops of Puy-en-Velay, Mende, and Viviers, which practically united Velay, Gévaudan, and Vivarais with the Crown. The occupation of this last region gave France almost the entire right bank of the Rhône. Philip the Fair had a bridgehead built at Villeneuve in front of Avignon, and Philip of Valois had another built at Sainte-Colombe in front of Vienne. The same king completed, in 1349, the acquisition of Montpellier. Finally, as a consequence of the unfortunate Treaty of Brétigny (1360), Rouergue was ceded to the king of England, and although Charles V reconquered it ten years later, it would henceforth follow the administrative destinies of Guyenne. The boundaries of Languedoc would not change again until the destruction of the province during the Revolution.

Except for the incursion of the Black Prince, who in 1355 pushed as far as Carcassonne, Languedoc would not be directly affected by the Hundred Years' War, but its loyalty and patriotism would play a crucial role in the fight against the English. It continued to provide money and men for national defense; cities fortified themselves everywhere to be able to stop the enemy, and our kings recognized these services by granting the States of the province an exceptional role, which we will return to.

It is interesting to note the importance that the ancient Voie Regordane, a Roman road attributed without evidence to Emperor Gordian, had during the Hundred Years' War. This road, leading from Nîmes to Clermont-Ferrand via Alès and the valley of the Allier, had long been one of the great pilgrimage routes, the via Tolosana. It linked the famous sanctuaries of Notre-Dame-du-Port, Brioude, and Le Puy-en-Velay, crossed the Cévennes, flowed into Nîmes, reached the sanctuary of Saint-Gilles, then that of Saint-Guilhem, from where, via Toulouse, it would cross the Pyrenees to arrive at Compostela. As this road, via Bourges and Orléans, led to Paris, it became, after the union of Languedoc, the great longitudinal axis of the royal domain and, during the Hundred Years' War, its major strategic and political artery since, on one hand, the Rhône valley was only partially French, and on the other, the English intercepted the routes of Aquitaine. It was there that Languedocians and Gascons would come to fight for the king of Bourges alongside Joan of Arc.

It is interesting to note the importance that the ancient Voie Regordane, a Roman road attributed without evidence to Emperor Gordian, had during the Hundred Years' War. This road, leading from Nîmes to Clermont-Ferrand via Alès and the valley of the Allier, had long been one of the great pilgrimage routes, the via Tolosana. It linked the famous sanctuaries of Notre-Dame-du-Port, Brioude, and Le Puy-en-Velay, crossed the Cévennes, flowed into Nîmes, reached the sanctuary of Saint-Gilles, then that of Saint-Guilhem, from where, via Toulouse, it would cross the Pyrenees to arrive at Compostela. As this road, via Bourges and Orléans, led to Paris, it became, after the union of Languedoc, the great longitudinal axis of the royal domain and, during the Hundred Years' War, its major strategic and political artery since, on one hand, the Rhône valley was only partially French, and on the other, the English intercepted the routes of Aquitaine. It was there that Languedocians and Gascons would come to fight for the king of Bourges alongside Joan of Arc.

The incorporation of Provence into the Crown in 1483 made Marseille the main French port on the Mediterranean, leading to the decline of Aigues-Mortes and Montpellier's trade. The prosperity that followed the end of the Hundred Years' War was once again ruined by the Wars of Religion, which took on a character of exceptional bitterness in the region. Generally speaking, Toulouse and Carcassonne remained Catholic and embraced the League's cause against Henry III; while the rest of the province, not to mention Agenais, was in the hands of Protestants, one can imagine the degree of fury reached during the struggle when, after the assassination of Henry III, the heir to the throne turned out to be a Protestant. The parliament of Toulouse, supported by a fanatical population, inflicted on the Huguenots harsher rigors than those of the Inquisition in the 10th century. As at that time, and for similar reasons, the local nobility provided the Reformed their military leaders.

The Edict of Nantes was merely a truce. In this region where the two confessions were so mixed, each claimed that the Edict was too favorable to the other, and taking advantage of Louis XIII's minority, the Protestants, who had retained their military organization, took up arms again. As soon as the king effectively took power, the Protestants were severely punished, but Montpellier only capitulated after a formal siege (1622). The peace of Montpellier hardly lasted, and the year 1627 saw the general uprising of the Protestants marked by the famous siege of La Rochelle. After the capitulation of that city (1628), the king turned against the Protestants of Languedoc, who everywhere opposed fierce resistance behind the walls that cities had built in the 16th century to stop the English and mercenaries. Louis XIII had Privas razed as an example, but immediately afterward, demonstrating the same admirable moderation he had shown to the inhabitants of La Rochelle, granted the Reformed the famous peace of Alès (1629), which strictly maintained the stipulations of the Edict of Nantes but ruined the Protestants' claims to form a state within a state.

The Edict of Nantes was merely a truce. In this region where the two confessions were so mixed, each claimed that the Edict was too favorable to the other, and taking advantage of Louis XIII's minority, the Protestants, who had retained their military organization, took up arms again. As soon as the king effectively took power, the Protestants were severely punished, but Montpellier only capitulated after a formal siege (1622). The peace of Montpellier hardly lasted, and the year 1627 saw the general uprising of the Protestants marked by the famous siege of La Rochelle. After the capitulation of that city (1628), the king turned against the Protestants of Languedoc, who everywhere opposed fierce resistance behind the walls that cities had built in the 16th century to stop the English and mercenaries. Louis XIII had Privas razed as an example, but immediately afterward, demonstrating the same admirable moderation he had shown to the inhabitants of La Rochelle, granted the Reformed the famous peace of Alès (1629), which strictly maintained the stipulations of the Edict of Nantes but ruined the Protestants' claims to form a state within a state.

The centralizing measures that Richelieu deemed necessary to take in Languedoc to prevent the recurrence of similar events, particularly by limiting the powers of the States, provoked initially passive resistance from part of the episcopate, the nobility, and the parliament; but this resistance took the form of rebellion when the Duke of Montmorency, governor of the province, sought to play his part in the vast aristocratic conspiracy to which Gaston d'Orléans lent his uncertain authority. The loyalty of the Protestants and communes ruined the hopes of the conspirators. Montmorency, defeated and captured at the Battle of Castelnaudary, was beheaded in the courtyard of the Capitole in Toulouse (1632). A weak echo of the Battle of Muret.

This is where it is appropriate to say a few words about the administration of the province. At its head was the governor, who, from 1526 to 1632, was always a Montmorency. Richelieu made the governor a mere decorative figure, replaced by the lieutenant general in the actual exercise of his functions. The parliament of Toulouse, the second oldest after that of Paris, founded in 1303 by Philip the Fair, abolished by the same king in 1312, was restored in 1419, but given that France was then engaged in the most critical period of the Hundred Years' War, it was only definitively reconstituted in 1443. Its magistrates were noted for their expertise, their uncompromising Catholicism, and in the 18th century, for their unreasonable pretensions and their opposition to the administrative and financial reforms contemplated by the monarchy, so much so that the popularity they earned at the time as opponents led to an ambiguity, and the Revolution would make this clear by sending 53 of them to the guillotine.

This is where it is appropriate to say a few words about the administration of the province. At its head was the governor, who, from 1526 to 1632, was always a Montmorency. Richelieu made the governor a mere decorative figure, replaced by the lieutenant general in the actual exercise of his functions. The parliament of Toulouse, the second oldest after that of Paris, founded in 1303 by Philip the Fair, abolished by the same king in 1312, was restored in 1419, but given that France was then engaged in the most critical period of the Hundred Years' War, it was only definitively reconstituted in 1443. Its magistrates were noted for their expertise, their uncompromising Catholicism, and in the 18th century, for their unreasonable pretensions and their opposition to the administrative and financial reforms contemplated by the monarchy, so much so that the popularity they earned at the time as opponents led to an ambiguity, and the Revolution would make this clear by sending 53 of them to the guillotine.

Languedoc was, from its union with the Crown, a "country of States," and the States of Languedoc early on had an importance commensurate with that of the province. The patriotism with which they voted, during the darkest moments of the Hundred Years' War, after the disasters of Crécy, Poitiers, and Azincourt, the necessary subsidies for national defense earned them, from our kings, a recognition from which they derived a renewed prestige and authority.

The States, which met annually, mostly in Montpellier or Pézenas, included 22 archbishops or bishops, 22 barons, and 44 deputies from the towns; the archbishop of Narbonne was its president. Their meetings were occasions for sumptuous ceremonies.

The main of the "franchises and liberties" of Languedoc consisted in the consent of taxes by the Estates, but when the monarchy, at the end of the 15th century, had regained sufficient strength to resume its task of centralization and unification, consent gradually became a mere bargaining tool intended to save face. However, even after the reforms of Richelieu, the Estates continued to serve effectively as an intermediary between the communes and the central power, to regulate the distribution of taxes according to the resources of each area, and, above all, to allocate part of the provincial budget in agreement with the intendant for the execution of important public works, foremost among them the famous Canal du Midi. The assembly, on the other hand, retained the power to express remarks or grievances that the King's Council examined with attention.

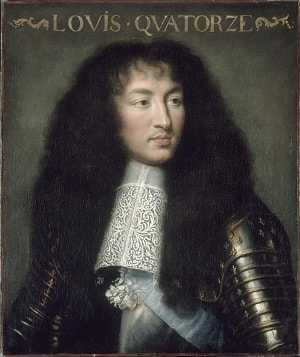

The franchises of the province also consisted of the significant remnants of autonomy that the communes had retained from the time when they were true Italian-style republics. Independently of the inconvenience these freedoms presented for sovereign power, they often resulted in the ruin of the communes' finances, which borrowed and taxed indiscriminately. Already Henry IV had begun to put them under guardianship; Louis XIV completed their subjugation by transforming (in 1692) elective municipal offices into venal positions, which was indeed an excess in the opposite direction.

The intendance of Languedoc, divided into two generalities (Montpellier and Toulouse), had, like other provinces, eminent holders (only eleven in 150 years) among whom were Daguesseau (1674-1685) and Basville (1685-1718), who, following the impetus given by Colbert, restored the forests, developed the industries of cloth, silk, and lace, and created the port of Sète. The prosperity due to these remarkable administrators only grew in the second half of the 18th century, and the reports of the last among them, Ballainvilliers (1786-1790), inform us that, once regional needs were met, the province's exports represented an annual profit of 66 million livres. The population then stood at 1,700,000 inhabitants; Toulouse had 60,000 and Montpellier 30,000.

The intendance of Languedoc, divided into two generalities (Montpellier and Toulouse), had, like other provinces, eminent holders (only eleven in 150 years) among whom were Daguesseau (1674-1685) and Basville (1685-1718), who, following the impetus given by Colbert, restored the forests, developed the industries of cloth, silk, and lace, and created the port of Sète. The prosperity due to these remarkable administrators only grew in the second half of the 18th century, and the reports of the last among them, Ballainvilliers (1786-1790), inform us that, once regional needs were met, the province's exports represented an annual profit of 66 million livres. The population then stood at 1,700,000 inhabitants; Toulouse had 60,000 and Montpellier 30,000.

The province's prosperity would have been even greater if the revocation of the Edict of Nantes and the Camisard War had not seriously affected it. For details on the events, one can refer to what we have said. It suffices here to say that, in trying to eliminate Protestantism, the State aimed to achieve a political and religious unity that would increase its power; it was merely applying the public law precept then universally recognized: cujus regio, ejus religio. Did not the religious organization of Protestants have something federal and democratic that was incompatible with the principle of absolute monarchy?

Finally, it is necessary to relate the revocation to other religious affairs and recall that Louis XIV, while targeting the Protestants, supported the liberties of the Gallican Church against the pope.

In any case, regarding the Cévennes, the Languedoc episcopate and the parliament of Toulouse merely exacerbated the measures taken against the Protestants, while Catholic merchants and artisans often saw in the revocation an opportunity to eliminate competitors. On the eve of the Revolution, while the government had renounced the religious struggle and practically recognized freedom of conscience, bishops and parliamentarians had not disarmed. On the other hand, it should be noted that, in general, this atrocious persecution had not diminished the loyalty of the Protestants who had not emigrated.

The beginnings of the Revolution were favorably received, but subsequently, it provoked, in this tormented country of resentments, very varied reactions. If the people of Toulouse who, in the 16th and 17th centuries, had been passionately Catholic, became equally passionately "sans-culotte," the rest of Languedoc was, in sum, the region of France where, after Brittany, Anjou, and Vendée, royalist resistance was most active. While this resistance was primarily caused by the anti-Catholic measures of the revolutionary assemblies, it is notable that it also manifested itself in the Cévennes, populated by Protestants. This did not prevent Catholics and Protestants from clashing in other circumstances, and while the Empire, restoring Catholicism alongside freedom of conscience, was a time of tranquility, the Restoration suddenly saw the passions that had been dormant reignite. And although today they confront each other only on the electoral ground, the tendencies of the past are still manifested by the sharply defined character of each political party, by the intransigence with which one is Catholic, Protestant, or non-believer.

The beginnings of the Revolution were favorably received, but subsequently, it provoked, in this tormented country of resentments, very varied reactions. If the people of Toulouse who, in the 16th and 17th centuries, had been passionately Catholic, became equally passionately "sans-culotte," the rest of Languedoc was, in sum, the region of France where, after Brittany, Anjou, and Vendée, royalist resistance was most active. While this resistance was primarily caused by the anti-Catholic measures of the revolutionary assemblies, it is notable that it also manifested itself in the Cévennes, populated by Protestants. This did not prevent Catholics and Protestants from clashing in other circumstances, and while the Empire, restoring Catholicism alongside freedom of conscience, was a time of tranquility, the Restoration suddenly saw the passions that had been dormant reignite. And although today they confront each other only on the electoral ground, the tendencies of the past are still manifested by the sharply defined character of each political party, by the intransigence with which one is Catholic, Protestant, or non-believer.

All of this is passionately argued and without nuance, as befits a people who have an appreciation for rhetorical controversies, complicated by local and personal rivalries, as the Meridional is individualistic. And yet, alongside the "militants" enlisted in a party, there are also many indifferent individuals, somewhat hedonistic as one can be in a country where life is relatively easy, and who, setting aside historical grudges, likely unknowingly revive the gentle manners of the time before the Albigensian Crusade.

These rivalries did not prevent Languedoc from prospering in the 19th century by developing its natural resources. Hydroelectric plants now complement local coal in the operation of factories; a significant effort, still insufficient, as shown by the flood of 1930, has been made for reforestation. The port of Sète has continued to grow.

However, the 19th century saw the traditional physiognomy of the region altered by the unprecedented development of vine cultivation in Lower Languedoc, and this fact has significantly separated this region from Toulouse. This distinction between Mediterranean Languedoc and Aquitaine Languedoc is such an evident reality that the province early on had two heads, Toulouse and Montpellier. If, from North to South, the plain and the mountain complement each other happily, it is mainly language and history that have united the East and the West.

Former holiday hotel with a garden along the Allier, L'Etoile Guest House is located in La Bastide-Puylaurent between Lozere, Ardeche, and the Cevennes in the mountains of Southern France. At the crossroads of GR®7, GR®70 Stevenson Path, GR®72, GR®700 Regordane Way, GR®470 Allier River springs and gorges, GRP® Cevenol, Ardechoise Mountains, Margeride. Numerous loop trails for hiking and one-day biking excursions. Ideal for a relaxing and hiking getaway.

Copyright©etoile.fr