Arts and architecture in the Cevennes |

The Cévennes and the Causses, riddled with caves, have not revealed, without anyone being able to say why, an artistic life comparable to that of Périgord or the Pyrenees. However, one can mention for the Bronze Age the treasure found on the causse Méjean near Mas-Saint-Chély (at the Mende museum), the treasure of the Capucins rise in Puy-en-Velay (at the museum in Lyon).

The Cévennes and the Causses, riddled with caves, have not revealed, without anyone being able to say why, an artistic life comparable to that of Périgord or the Pyrenees. However, one can mention for the Bronze Age the treasure found on the causse Méjean near Mas-Saint-Chély (at the Mende museum), the treasure of the Capucins rise in Puy-en-Velay (at the museum in Lyon).

The Gallo-Roman period is represented by the magnificent monuments of Nîmes and by the countless objects found in the Nîmes region, some of purely Roman manufacture, others imported from Greece or Italy (the Maison Carrée museum and the archaeological museum). The acropolis of Ensérune, near Béziers, has provided a large number of remarkable vases imported from Greece and gathered at the Mouret museum. The workshops of sigillated pottery in Banassac (Lozère) and Graufesenque, near Millau, spread their beautiful products throughout the Languedoc region (the museums of Mende and Rodez).

Religious architecture. — After the night of barbarian invasions and the high Middle Ages, the Carolingian renaissance finally came. But in the poor mountains of the Cévennes, as on the coast exposed to all forms of degradation, this renaissance has left fewer traces than elsewhere. However, one can attribute the X century to the baptistery of Mélas and the oldest part of Saint-Michel d'Aiguilhe in Puy-en-Velay; to the XI century, the crypt of Cruas and the baptistery of Puy-en-Velay, the church of Quarante, the nave of Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert, perhaps the chapel of Notre-Dame de Vallée-Française.

Religious architecture. — After the night of barbarian invasions and the high Middle Ages, the Carolingian renaissance finally came. But in the poor mountains of the Cévennes, as on the coast exposed to all forms of degradation, this renaissance has left fewer traces than elsewhere. However, one can attribute the X century to the baptistery of Mélas and the oldest part of Saint-Michel d'Aiguilhe in Puy-en-Velay; to the XI century, the crypt of Cruas and the baptistery of Puy-en-Velay, the church of Quarante, the nave of Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert, perhaps the chapel of Notre-Dame de Vallée-Française.

The XII century, especially in its second half, sees the diffusion of Romanesque art; but due to the poverty of resources, its productions remain, in general, so simple that they cannot be attributed to a specific school: an apse, a nave without side aisles, sometimes two false transepts covered with transverse vaults, a portal without sculptures are the unchanging elements of many churches throughout southern France. The Auvergne school, few in number but so original, influenced the churches of Chamalières, Saint-Paulien, and the cathedral of Puy-en-Velay, which remains, in many respects, an exceptional building.

Bas-Languedoc, richer, more populated, endowed with large cities, has left us more considerable monuments. Churches with side aisles are more frequent: churches in Béziers, Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert, Espondeilhan, Quarante. Similarly, the Rhône valley: Cruas, Bourg-Saint-Andéol. But some quite large cathedrals lack collateral (Agde, Maguelone). These monuments, built in a region where ideas circulated as easily as people, denote strictly Mediterranean influences; Provençal influences and, higher up, Carolingian influences, that is to say, imperial and Gallo-Roman. The famous portal of Saint-Gilles resembles that of Arles and the decoration of the apse of Saint-Jacques in Béziers belongs to the Provençal school that has spread to Alet in the Aude valley. The richly composed absides of Cruas, Bourg-Saint-Andéol, Quarante, and Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert belong to Lombard art that, over Bas-Languedoc, conquered Catalonia.

In the Causses region, large abbey churches are primarily Benedictine or Cistercian constructions (Nant, Sylvanès). Likewise, Saint-Salvi d'Albi. The one in Conques-en-Rouergue is an exceptional building that resembles Saint-Sernin in Toulouse, Moissac, and Beaulieu. Like Provence, Bas-Languedoc preserves a multitude of small rural Romanesque chapels.

All of southern France remained faithful, during the Gothic period, to the Romanesque art that suited its habits of simplicity.

All of southern France remained faithful, during the Gothic period, to the Romanesque art that suited its habits of simplicity.

The rib vault does, however, appear in isolation, to solve specific problems, at the end of the XII century, that is to say, with a fifty-year delay compared to Île-de-France, and it is still uncertain whether these examples derive from Parisian or Champagne art (the transepts of Maguelone, the porch of Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert).

Some great monuments do belong to the Gothic style of Northern France: cathedrals in Montpellier, Rodez, Mende, Lodève, but only the one in Rodez is truly successful; all the others suffer from some poverty in planning and some dryness in execution. To the cathedral of Rodez, one should, however, add the choir of the cathedral of Narbonne, which reproduces those of Limoges and Clermont-Ferrand.

However, most often, Gothic churches belong to the southern Gothic style and this style is so uniform that this designation has spared us from describing the structure of these edifices. They consist primarily of a nave flanked by side chapels and a polygonal apse that is narrower and lower than the nave; there is no ambulatory, no transept, nor side aisles. Sometimes the apse is flanked by small absidioles that open like it in the nave (Saint-Vincent and Saint-Michel de Carcassonne, Frontignan, Saint-Sévère d'Agde, Cruzy).

However, most often, Gothic churches belong to the southern Gothic style and this style is so uniform that this designation has spared us from describing the structure of these edifices. They consist primarily of a nave flanked by side chapels and a polygonal apse that is narrower and lower than the nave; there is no ambulatory, no transept, nor side aisles. Sometimes the apse is flanked by small absidioles that open like it in the nave (Saint-Vincent and Saint-Michel de Carcassonne, Frontignan, Saint-Sévère d'Agde, Cruzy).

The prototype of the southern Gothic style is obviously the cathedral of Albi, begun at the end of the XIII century; but the idea of the nave without collateral flanked by side chapels had already been realized in the XII century at the Cistercian abbey of Sylvanès in Rouergue, and this abbey only reproduced that of Fontenay in Burgundy. But, whatever the origin of this "formula," it has only flourished in southern France. And Mr. Emile Mâle is probably right when he attributes this favor to the convenience that these naves offered for preaching in a region where the religious authorities primarily focused on the repression of the remnants of Albigensianism.

These churches are characterized not only by the structure we have just indicated but also by their proportions: the height indeed decreases in relation to the width and these two dimensions tend towards equality, which is a complete contrast to the slender lines of the northern churches. Furthermore, in the full XIV century, the broken cradle on doubleaux remains in use on the nave: Cruzy, Frontignan.

Among the monastic constructions of the Gothic period, the charterhouse of Villefranche-de-Rouergue deserves special mention for its importance and remarkable state of preservation. Just as it remained faithful to the Romanesque style during the Gothic period, Languedoc preserved the Gothic style, or at least its essential principle, the ribbed vault, well into the XVII century (cathedrals of Alès, Castres, Uzès, the latter only having side aisles, church of Lunel, etc.). There are, of course, classical churches analogous to those in Northern France. But, overall, the churches of the classical era are few in number because the southerners felt no need to reconstruct a church to follow the fashion, and, without the destructions caused by the Protestants in the XVI century, classical churches would be even fewer.

Among the monastic constructions of the Gothic period, the charterhouse of Villefranche-de-Rouergue deserves special mention for its importance and remarkable state of preservation. Just as it remained faithful to the Romanesque style during the Gothic period, Languedoc preserved the Gothic style, or at least its essential principle, the ribbed vault, well into the XVII century (cathedrals of Alès, Castres, Uzès, the latter only having side aisles, church of Lunel, etc.). There are, of course, classical churches analogous to those in Northern France. But, overall, the churches of the classical era are few in number because the southerners felt no need to reconstruct a church to follow the fashion, and, without the destructions caused by the Protestants in the XVI century, classical churches would be even fewer.

However, classic architecture is dignifiedly represented by old Montpellier: this city populated by nobles, bourgeois, officials, professors, and lawyers was almost entirely rebuilt after the siege of 1622, with an uncommon luxury in the region. Powerful and elegant architecture, the result of the abstract work of refined designers, because the narrowness of the streets and courtyards prevents any overall view. In any case, the hotels of Montpellier, much more French than those of Aix-en-Provence which are more Italian, constitute one of the most beautiful classical decors one can see in France after Bordeaux and Nancy. Pézenas also offers a considerable number, given the city's lesser importance, of similar hotels, but which, having frequently fallen into the hands of small people, are today quite dilapidated and disfigured.

Public architecture. — This part of France has preserved a considerable number of ancient bridges, often very beautiful: the most famous are the Pont du Gard, a masterpiece of Roman architecture, and the Pont Saint-Esprit, which gave its name to the town that formed at one of its ends. Since its partial destruction, the bridge in Avignon no longer connects with Languedoc.

Public architecture. — This part of France has preserved a considerable number of ancient bridges, often very beautiful: the most famous are the Pont du Gard, a masterpiece of Roman architecture, and the Pont Saint-Esprit, which gave its name to the town that formed at one of its ends. Since its partial destruction, the bridge in Avignon no longer connects with Languedoc.

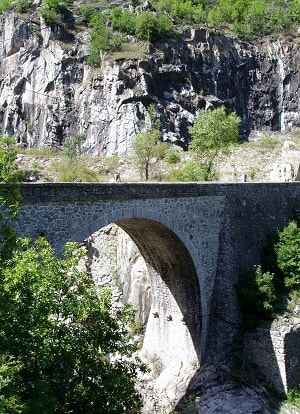

Another very beautiful Roman bridge can be seen near Viviers. However, it is primarily Gothic works that one encounters: Béziers, Le Puy-en-Velay, Mende, Espalion, Estaing, Entraygues, Olargues, Camarès, Quezac, etc. Many of them, very elevated above the torrents they cross, with a large central arch and a very pronounced hump, have a superb appearance and wonderfully complement the landscapes where they were built. Many small similar bridges, which are part of rural paths, built with less care than those on the main roads, only date from the classical period when the network of the Middle Ages was completed.

In the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries, several large cities: Albi, Béziers, Nîmes, Alès, Le Puy-en-Velay, Pézenas erected important town halls. Montpellier and Nîmes created in the 18th century two of the most beautiful public gardens one can see in France. The Jesuit colleges of Tournon, Montpellier, Albi, Rodez have not changed their purpose and today serve as high schools. The one in Sorèze, of Benedictine origin, has had a different history that has only added to its old celebrity.

Public architecture is also represented by ancient halls that are not among the oldest in France: Revel, Anduze, Langogne. The region described in this guide does not offer the multitude of bastides founded in the 13th century that one finds in the Southwest; therefore, one sees much less of these old cities built on a regular plan, with the central square surrounded by arcades or "couverts," and the examples are less typical. Such squares can be seen in Revel, Uzès, and Millau. However, the Place Notre-Dame in Villefranche-de-Rouergue is one of the most beautiful of its kind, but it should be noted that we are much closer to Gascony here than elsewhere. The lower town of Carcassonne finally offers the largest and most beautiful example of French urban planning from the 13th century.

Military architecture. — Military architecture is abundantly represented in this region. The Rhône valley had, like the Rhine, its rival fortresses. The interior of Vivarais, Velay, Gévaudan, and Rouergue, located outside the main thoroughfares, were less fortified against outside enemies than for the needs of local quarrels. In Bas-Languedoc, the memories of the Albigensian war and even the Protestant wars persist vividly in the fortifications; finally, the coast has always been, like the Rhône in the Middle Ages, a border that it was the king's duty to defend. Hence the diversity of monuments. Fortified churches are particularly numerous in Languedoc; they alone formed the defense of many villages and served as citadels for small towns provided with walls.

Military architecture. — Military architecture is abundantly represented in this region. The Rhône valley had, like the Rhine, its rival fortresses. The interior of Vivarais, Velay, Gévaudan, and Rouergue, located outside the main thoroughfares, were less fortified against outside enemies than for the needs of local quarrels. In Bas-Languedoc, the memories of the Albigensian war and even the Protestant wars persist vividly in the fortifications; finally, the coast has always been, like the Rhône in the Middle Ages, a border that it was the king's duty to defend. Hence the diversity of monuments. Fortified churches are particularly numerous in Languedoc; they alone formed the defense of many villages and served as citadels for small towns provided with walls.

Countless are also the towns that have preserved at least part of their walls, most often built in the 14th century, and these remains reveal the already harsh character by itself of so many southern sites. Cordes in Albigeois, La Couvertoirade in Rouergue and Aigues-Mortes, not to mention Carcassonne, have particularly interesting walls. Let's add the beautiful gates of Marvejols.

Many castles are adjacent to a town: La Voulte-sur-Rhône, Largentières, Beaucaire, Tournon, Aubenas, or even planted in the town: Uzès, Yssingeaux. Those in Largentières and Yssingeaux are due to the bishops of Viviers and Le Puy-en-Velay; the episcopal castle of Albi is one of the most beautiful fortresses in all of southern France.

But in this mountainous country, there is hardly a well-placed peak that a thin local lord has not chosen to retreat to, and these rough buildings, more or less ruined, fit much better into the surrounding landscape than in the soft Touraine: Polignac, Brissac, Cabrières, Crussol, Bournazel, Castelnau-de-Lévis, Castelbouc, Lacaze, Séverac, Estaing, Penne, Bruniquel, so many sonorous names like musket shots. Many of these castles also have parts from the 15th or 16th century, and they should not be neglected if one wants to get an accurate idea of Renaissance art in the region.

Many castles are adjacent to a town: La Voulte-sur-Rhône, Largentières, Beaucaire, Tournon, Aubenas, or even planted in the town: Uzès, Yssingeaux. Those in Largentières and Yssingeaux are due to the bishops of Viviers and Le Puy-en-Velay; the episcopal castle of Albi is one of the most beautiful fortresses in all of southern France.

But in this mountainous country, there is hardly a well-placed peak that a thin local lord has not chosen to retreat to, and these rough buildings, more or less ruined, fit much better into the surrounding landscape than in the soft Touraine: Polignac, Brissac, Cabrières, Crussol, Bournazel, Castelnau-de-Lévis, Castelbouc, Lacaze, Séverac, Estaing, Penne, Bruniquel, so many sonorous names like musket shots. Many of these castles also have parts from the 15th or 16th century, and they should not be neglected if one wants to get an accurate idea of Renaissance art in the region.

Finally, as in Auvergne, isolated or adjoining fortified houses can be found in Velay, Gévaudan, and Vivarais. Here, as in the rest of the South, these constructions lag significantly behind the military architecture of the North. This is because the resources of the builders were more limited, and also because the steepness of the positions facilitated the engineers' tasks. One will not cease to build poorly defended square towers at the throat, poorly protected gates, too large windows. Some fortresses, however, are exceptions, notably the tower of Constance in Aigues-Mortes and the castle of Najac: but these are precisely royal constructions, built by engineers from the North. Like the other borders, the coast was put in a state of defense by Louis XIV and Louis XV (forts of Sète and Cap d'Agde). It should be noted as a curiosity the citadels of Alès, Nîmes, Montpellier built in the 17th century to keep the Protestants at bay.

Former holiday hotel with a garden along the Allier, L'Etoile Guest House is located in La Bastide-Puylaurent between Lozere, Ardeche, and the Cevennes in the mountains of Southern France. At the crossroads of GR®7, GR®70 Stevenson Path, GR®72, GR®700 Regordane Way, GR®470 Allier River springs and gorges, GRP® Cevenol, Ardechoise Mountains, Margeride. Numerous loop trails for hiking and one-day biking excursions. Ideal for a relaxing and hiking getaway.

Copyright©etoile.fr