History of Lozere |

The history of Lozère is profoundly influenced by its mountainous geography, which has long isolated and preserved its territories. Inhabited since prehistoric times, as evidenced by the megaliths, it was an important crossroads in the Middle Ages, notably with the passage of Saint-Gilles and the routes of Saint James, leaving behind a rich religious heritage. The region was also the scene of the bloody episode of the Beast of Gévaudan in the 18th century, which reinforced its legend. In the 19th century, rural exodus was significant, but paradoxically contributed to the preservation of its natural landscapes (Cévennes, Aubrac, Causses). The architectural heritage is characterized by granite and schist, featuring typical farms and small Romanesque churches. The creation of the Cévennes National Park underscores the commitment to preserving this territory, which boasts exceptional fauna and flora.

Before the Roman conquest, the land that today forms the department of Lozere was inhabited by the Gabali or Gabales, a name that means mountaineers or inhabitants of the highlands in the Celtic language. Caesar, Ptolemy, Strabo, and Pliny mention this people, who were bordered to the north by the Arverni, to the west by the Vellaves and Helvii; to the south by the Volces, and to the east by the Ruthenians. They had their city Gabalum, now Javols. A free people like the Arverni (Arverni and Gabali liberi, according to Pliny's expression), they were companions of Bellovese and crossed the Alps following Asdrubal. Rome always had them as enemies, never as subjects; and when later, having taken sides with the Allobroges, they were defeated, they remained independent.

Before the Roman conquest, the land that today forms the department of Lozere was inhabited by the Gabali or Gabales, a name that means mountaineers or inhabitants of the highlands in the Celtic language. Caesar, Ptolemy, Strabo, and Pliny mention this people, who were bordered to the north by the Arverni, to the west by the Vellaves and Helvii; to the south by the Volces, and to the east by the Ruthenians. They had their city Gabalum, now Javols. A free people like the Arverni (Arverni and Gabali liberi, according to Pliny's expression), they were companions of Bellovese and crossed the Alps following Asdrubal. Rome always had them as enemies, never as subjects; and when later, having taken sides with the Allobroges, they were defeated, they remained independent.

Sheltered behind their snow-covered mountains, they governed themselves by their own laws and obeyed only chiefs elected by them. It appears that their land abounded in silver mines, already exploited during Roman times. Pliny praises the cheeses from Lozere's mountains (mons Lezuroe). This land is one of those that have preserved the most traces of the Celtic era. In Javols, at Aumide, in Fonds, in Grezes, in Malavillette, at Montet, one can still see dolmens, menhirs, druidic stones, and it is believed that the spring of Canourgue is a Gallic spring. In Sainte-Helene, on the right bank of the Lot, travelers stop in front of a "peulven" that is called in the country "lou Bertet de las fadas", the Spindle of the Fairies.

After leaving garrisons in Narbonne and in the Province, Caesar crossed the Cevennes and camped in the land of the Gabales before entering Arvernie. It is said that in the plain of Montbel, near the forest of Mercoire, the Roman general had his legions rest. Surprised by this sudden appearance, the Gabales took up arms, forcing their neighbors the Helvians, who had declared for Caesar, to return to their walls (intra oppida murosque); then they went to join the national army, assembled by Vercingetorix.

After leaving garrisons in Narbonne and in the Province, Caesar crossed the Cevennes and camped in the land of the Gabales before entering Arvernie. It is said that in the plain of Montbel, near the forest of Mercoire, the Roman general had his legions rest. Surprised by this sudden appearance, the Gabales took up arms, forcing their neighbors the Helvians, who had declared for Caesar, to return to their walls (intra oppida murosque); then they went to join the national army, assembled by Vercingetorix.

After the disaster of Alesia, those among them who had survived the ruin of their homeland returned to their mountains; but even there, victorious Rome had to reckon with them and respect their freedoms and laws. However, Augustus freed them from the ties that bound them to the Arverni and included them in Aquitaine. Then Gabalum, a Roman colony, became the residence of a praetor or proconsul. There was a temple, a palace, a circus, of which the remains are still visible; a castrum rose in Valdonnez, and the great Roman road, opened by Agrippa, which led from Lugdunum to the city of the Tectosages (Toulouse), had, between Mas de la Tieule and Bouchet, a branch that led to Gabalum. Gradually, Roman civilization tempered the harshness and severity of this land.

In Strabo's time, the arts and sciences had penetrated there, and the inhabitants began to speak Latin. They engaged in agriculture, trade, and the exploitation of mines; but their riches brought them misfortune by exciting the greed and avarice of the Roman praetors, and it was to avenge their exactions that they revolted under Tiberius.

Soon Christianity came to complete the work of colonization, and this free and proud people, of whom Rome had conquered only the territory, bowed their heads under the yoke of the cross. According to some, it was to Saint Martial, according to others, to Saint Severin, that they owed their knowledge of the Gospel. In any case, the city of the Gabales had, in the 3rd century, its church and its episcopal seat under the metropolitan of Bourges, and the persecution had made more than one martyr there. When the Vandals appeared for the second time in this land in the 5th century, Saint Privat was the bishop there. After the sack of Gabalum by these barbarians, he took refuge with his flock in the small fortress of Grezes (Gredonense castellum), where he sustained a siege against the enemy and forced them to retreat.

However, in the 6th century, there were still remnants of the ancient druidic religion in this land. Every year, the people went to a pond on Mount Helanus (Lake Saint-Andeol), where they threw sacrifices, some linen and clothing, others cheese, bread, and wax. Then, to divert the Gabales from this crude cult, the holy bishop Evanthius had a church built a short distance from Mount Helanus, where he urged the people to come and offer to the true God what they intended for the pond. Thus Christianity turned the most crude practices of paganism to its advantage.

However, in the 6th century, there were still remnants of the ancient druidic religion in this land. Every year, the people went to a pond on Mount Helanus (Lake Saint-Andeol), where they threw sacrifices, some linen and clothing, others cheese, bread, and wax. Then, to divert the Gabales from this crude cult, the holy bishop Evanthius had a church built a short distance from Mount Helanus, where he urged the people to come and offer to the true God what they intended for the pond. Thus Christianity turned the most crude practices of paganism to its advantage.

At the fall of the Roman Empire, the Visigoths took over the land of the Gabales; but Clovis drove them out. Then, as we learn from Gregory of Tours, this land was called Terminus Gabalitanus or Regio Gabalitana. Later, it formed Pagus Gavaldanus, which is mentioned by medieval writers; hence the modern name Gevaudan. Under the Frankish kings, Gevaudan had particular counts. In the time of Sigebert, king of Austrasia, it was governed by a certain Pallade, originally from Auvergne. A violent and impetuous man, this Pallade, according to the old chroniclers, vexed and pillaged the people. Accused before the king by Bishop Parthenus, he forestalled his punishment by stabbing himself with his sword.

At the end of the 6th century, under the reign of Childebert, another count named Innocent governed this land as a worthy successor to Pallade. He persecuted among others Saint Louvent (Lupentius), abbot of the monastery of Saint-Privat of Gabalum (Gabalitanoe urbs), and accused him, to curry favor with Queen Brunehaut, of having spoken ill of this princess and of the court of Austrasia. This abbot, having been summoned to Metz, where Brunehaut was, justified himself and was sent back acquitted; but he could not escape the count's vengeance, who was waiting for him upon his return, seized him and took him to Pont-Yon in Champagne, where, after various torments he made him suffer, he allowed him to leave. It was only a trap, for scarcely had the poor monk been freed and departed when the count pursued him, and having surprised him at the crossing of the river Aisne, he cut his throat and threw his body into the river. After his crime, the count presented himself at the court of Austrasia. It has been claimed that he was rewarded with the bishopric of Rodez, but this fact is far from proven.

At the end of the 6th century, under the reign of Childebert, another count named Innocent governed this land as a worthy successor to Pallade. He persecuted among others Saint Louvent (Lupentius), abbot of the monastery of Saint-Privat of Gabalum (Gabalitanoe urbs), and accused him, to curry favor with Queen Brunehaut, of having spoken ill of this princess and of the court of Austrasia. This abbot, having been summoned to Metz, where Brunehaut was, justified himself and was sent back acquitted; but he could not escape the count's vengeance, who was waiting for him upon his return, seized him and took him to Pont-Yon in Champagne, where, after various torments he made him suffer, he allowed him to leave. It was only a trap, for scarcely had the poor monk been freed and departed when the count pursued him, and having surprised him at the crossing of the river Aisne, he cut his throat and threw his body into the river. After his crime, the count presented himself at the court of Austrasia. It has been claimed that he was rewarded with the bishopric of Rodez, but this fact is far from proven.

United with Aquitaine, this land followed its fate: it successively obeyed the kings of Aquitaine and the counts of Toulouse. Raymond of Saint-Gilles, one of them, allegedly alienated it in favor of the bishops of Mende. However, in the 11th century, a certain Gilbert, who married Tiburge, countess of Provence, called himself the count of Gevaudan. This Gilbert left a daughter who, married to Raymond Berenger, count of Barcelona, brought him all his rights over Gevaudan; but the bishop of Mende also claimed to be lord and count of the land. This led to long disputes with the counts of Barcelona, who nonetheless continued to enjoy the direct lordship of Gevaudan, where they owned the castle of Grezes.

Jacques, king of Aragon and count of Barcelona, ceded, in 1223, this castle and Gevaudan to the bishop and the chapter of Mende; "but there is reason to believe," says a historian, "that this cession concerned only the lordly title, and that Jacques reserved the useful domain, since, by a transaction made in 1255 with Saint Louis, the king of Aragon then renounced not only his rights over the land of Grezes, but also all those he had over Gevaudan." From then on, it was against the kings of France that the bishop of Mende had to assert his claims; but the struggle was unequal. After having preserved sovereignty over the land until 1306, he had to, to better secure possession of the rest, cede half to King Philip the Fair, who left him the title of count of Gevaudan.

Jacques, king of Aragon and count of Barcelona, ceded, in 1223, this castle and Gevaudan to the bishop and the chapter of Mende; "but there is reason to believe," says a historian, "that this cession concerned only the lordly title, and that Jacques reserved the useful domain, since, by a transaction made in 1255 with Saint Louis, the king of Aragon then renounced not only his rights over the land of Grezes, but also all those he had over Gevaudan." From then on, it was against the kings of France that the bishop of Mende had to assert his claims; but the struggle was unequal. After having preserved sovereignty over the land until 1306, he had to, to better secure possession of the rest, cede half to King Philip the Fair, who left him the title of count of Gevaudan.

In the 14th and 15th centuries, this land was ravaged by the English, and by civil and religious wars in the following two centuries. Then, like the valleys of the Alps, the Cevennes were populated by Albigensians and Waldensians whose families had taken refuge in these mountains during the persecution; but the inquisition also pursued them, and many victims perished on the pyre or under the knife in those terrible days that followed Saint Bartholomew's Day. However, the religious took up arms. After having become masters of Marvejols and Quezac (1562), they marched on Mende, which opened its doors to them, and from there to Chirac; but as the place was about to surrender, Captain Treillans, who commanded a Catholic force, arrived to their aid and forced the besiegers to retreat. Continuing his success, he recaptured Mende, where two other Catholic leaders, d'Apcher and Saint-Remisi, came to join him.

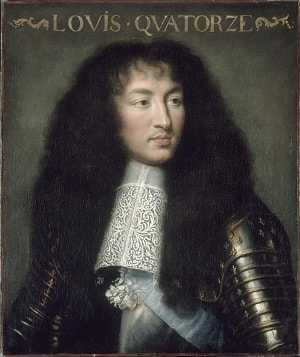

Soon the Protestants presented themselves again before Chirac: the city was taken and set ablaze. More than eighty Catholics perished there; the church was burned and the square was dismantled. From there, the religious marched on Mende; but d'Apcher, who had locked himself in with several noblemen from the rear, made a good stand, and the capital of Gevaudan remained in the hands of the Catholics. The Edict of Nantes (1598) came; but the tranquility enjoyed by the religious in the Cevennes was not to last. Constantly threatened in their privileges, their freedom, and their lives, patient and faithful, they relied on the faith of treaties and on the memory of the services they had rendered to the monarchy by refusing to take part in the revolt of Montmorency, and later in that of Conde. However, persecution was near. Colbert, who foresaw that this would result in the emigration of a primarily industrial population and the export of large capital, opposed it with all his power. "You are king," he said to Louis XIV, "for the happiness of the world, and not to judge the faiths." But the advice of Madame de Maintenon prevailed, and the Edict of Nantes was revoked (1685).

Soon the Protestants presented themselves again before Chirac: the city was taken and set ablaze. More than eighty Catholics perished there; the church was burned and the square was dismantled. From there, the religious marched on Mende; but d'Apcher, who had locked himself in with several noblemen from the rear, made a good stand, and the capital of Gevaudan remained in the hands of the Catholics. The Edict of Nantes (1598) came; but the tranquility enjoyed by the religious in the Cevennes was not to last. Constantly threatened in their privileges, their freedom, and their lives, patient and faithful, they relied on the faith of treaties and on the memory of the services they had rendered to the monarchy by refusing to take part in the revolt of Montmorency, and later in that of Conde. However, persecution was near. Colbert, who foresaw that this would result in the emigration of a primarily industrial population and the export of large capital, opposed it with all his power. "You are king," he said to Louis XIV, "for the happiness of the world, and not to judge the faiths." But the advice of Madame de Maintenon prevailed, and the Edict of Nantes was revoked (1685).

For a long time, the Protestants of Dauphine and Vivarais had revolted against the revocation of the edict, which those in the Cevennes, still submissive, had not thought to disturb. "Nevertheless," says Rabaut Saint-etienne, "they were spared then because it was undoubtedly feared that the mistreatment suffered by their brothers would throw them into despair. They were even allowed to convene a general assembly of deputies and noblemen from their province to pass a loyalty act to the king. "This assembly took place in Colognac in September 1683. Fifty Protestant pastors, fifty-four noblemen, thirty-four lawyers, doctors or notable bourgeois protested their attachment to the king, urging all their co-religionists to moderation and patience.

After the Peace of Ryswick (1697), the Protestants hoped again; but, instead of being favorable to them, this peace turned against them, and the ills they had suffered since the revocation, which had somewhat eased during the war, renewed with more violence than ever. Pressed to abjure, they replied that they were ready to sacrifice their lives for the king, but that their conscience belonged to God, and they could not dispose of it. Then terror and proscription reigned in this land.

At first, they sent them dragons to convert them. These booted missionaries, as they called them, entered houses with swords in hand: "Kill! Kill!" they shouted, or "Catholic!" That was their watchword. These swift methods were not enough, so other methods were invented: these poor people were hanged by their feet from their chimneys to suffocate them with smoke; others were thrown into wells; some had their nails pulled out or were pierced from head to toe with needles and pins. This was how signatures were sometimes extorted from them; but these conversions by dragon were only hypocrites. Such was, at the beginning of the 18th century, the fate of the Protestants in the Cevennes, and not only were they overburdened with soldiers, but also with taxes. The priests, abusing their influence, imposed an extraordinary tax on them, and more than twenty parishes in Gevaudan suddenly found themselves ruined by these exactions.

At first, they sent them dragons to convert them. These booted missionaries, as they called them, entered houses with swords in hand: "Kill! Kill!" they shouted, or "Catholic!" That was their watchword. These swift methods were not enough, so other methods were invented: these poor people were hanged by their feet from their chimneys to suffocate them with smoke; others were thrown into wells; some had their nails pulled out or were pierced from head to toe with needles and pins. This was how signatures were sometimes extorted from them; but these conversions by dragon were only hypocrites. Such was, at the beginning of the 18th century, the fate of the Protestants in the Cevennes, and not only were they overburdened with soldiers, but also with taxes. The priests, abusing their influence, imposed an extraordinary tax on them, and more than twenty parishes in Gevaudan suddenly found themselves ruined by these exactions.

In June 1702, poor peasants who could not pay were hanged, and those from nearby villages rose up, surprising the tax collectors at night and hanging them from trees with their rolls around their necks; and as they had disguised themselves by wearing two shirts, one over their clothes and the other on their heads, they were called Camisards, from the word "camise" (the local dialect for shirt). However, historians differ on the origin of this word: some derive it from the word "cami" (path), others trace it back to the siege of La Rochelle, where the Protestants who attempted to rescue that place covered themselves with a shirt to be recognized; others finally claim that since the camisards were mostly dressed like the peasants of the Cevennes who at that time wore a cloth coat resembling a shirt, they derived their name from that. In any case, it is certain that this nickname was particular to those from the Cevennes.

However, the persecution did not relent. The prisons were overflowing with Protestants; their properties were confiscated. Family fathers and old men were condemned to the galleys; others perished in tortures: flayed, burned, or hanged. A poor girl was executed at Pont-de-Montvert; another was whipped by the hand of the executioner. Every day there were proscriptions and victims. Children were torn from their mothers' arms and the mothers were thrown into convents to be converted. "Moreover," said the learned Tollius, "children were turned against their parents by emancipating them, despite their young age." More temples than convents; no other burial place than the highways; everywhere the inquisition with its swift missionaries. Such are, in essence, the details that Protestant historians agree on.

However, the persecution did not relent. The prisons were overflowing with Protestants; their properties were confiscated. Family fathers and old men were condemned to the galleys; others perished in tortures: flayed, burned, or hanged. A poor girl was executed at Pont-de-Montvert; another was whipped by the hand of the executioner. Every day there were proscriptions and victims. Children were torn from their mothers' arms and the mothers were thrown into convents to be converted. "Moreover," said the learned Tollius, "children were turned against their parents by emancipating them, despite their young age." More temples than convents; no other burial place than the highways; everywhere the inquisition with its swift missionaries. Such are, in essence, the details that Protestant historians agree on.

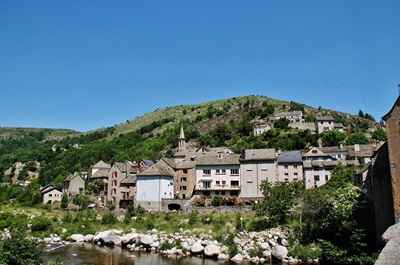

At that time, Gevaudan was divided into high and low lands: the high land was almost entirely in the mountains of Margeride and Aubrac; the low land was part of the high Cevennes and occupied the mountain of Lozere. This mountain forms a chain known by various names, extending to the borders of Rouergue and the diocese of Alais or low Cevennes. It is here that Le Pont-de-Montvert and Bouges are located, one of the mountains of Lozere, whose highest peak, covered with beech woods, took the name of Altefage, a corrupted word from Latin, meaning an elevated beech. These wild places served as refuges for the outcasts. Like Christians in the catacombs, they gathered there at night, reading the Bible, singing psalms, and encouraging each other to courage and patience.

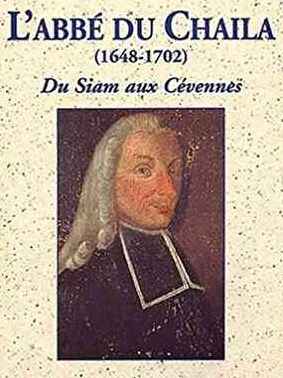

Now, there was at Pont-de-Montvert a priest from a noble and warrior family: he was called Abbe du Chayla. He was a naturally imperious, dark, and violent man; however, following serious illnesses, he relaxed his austerities. "He led, says his biographer, a less harsh life." He rode horseback, practiced a little less abstinence, fasting, and treated his guests well. It seems he also liked to gamble. He had been a missionary in Siam. Upon returning to his homeland, he was appointed inspector of the missions in the Cevennes; driven by a zeal that several, his biographer adds, have described as indiscreet, he waged a harsh war against the Protestants. "To succeed better, he took with him a flying mission, composed of several missionaries, both secular and regular, and traveled everywhere there were heretics to fight; but instead of working for the good of religion and the State, his mission only created enemies for them. He had made his castle a prison, and what was said about the tortures he inflicted on those he wanted to convert made him the terror of the region.

Now, there was at Pont-de-Montvert a priest from a noble and warrior family: he was called Abbe du Chayla. He was a naturally imperious, dark, and violent man; however, following serious illnesses, he relaxed his austerities. "He led, says his biographer, a less harsh life." He rode horseback, practiced a little less abstinence, fasting, and treated his guests well. It seems he also liked to gamble. He had been a missionary in Siam. Upon returning to his homeland, he was appointed inspector of the missions in the Cevennes; driven by a zeal that several, his biographer adds, have described as indiscreet, he waged a harsh war against the Protestants. "To succeed better, he took with him a flying mission, composed of several missionaries, both secular and regular, and traveled everywhere there were heretics to fight; but instead of working for the good of religion and the State, his mission only created enemies for them. He had made his castle a prison, and what was said about the tortures he inflicted on those he wanted to convert made him the terror of the region.

One day, at the head of a company of soldiers, he surprised an assembly of Protestants in the mountains. More than sixty people of both sexes who had gathered to pray were taken; the abbot began by hanging some of them and had the others taken to his castle; however, several managed to escape, summoned their brothers, and recounted what they had suffered. They said that the abbot would split beams with iron wedges and then force his prisoners to put their fingers in those splits from which he would remove the wedges. This was called the "Abbe du Chayla's stocks."

At this terrible account, anger and despair were painted on all faces. Everyone swore to avenge their persecuted brothers. They armed themselves and went to the entrance of the night at Pont-de-Montvert, in front of the castle: silence reigned there, the doors were barricaded: the abbot, who had heard of the conspiracy, had prepared to resist. He had with him a few soldiers and determined servants ready to sell their lives dearly. But the assailants broke down the doors and set fire to the castle. The roof was already in flames; the abbot tried to escape with a rope ladder through a window that opened onto the garden; but, slipping, he fell and broke his leg. Nevertheless, he managed to crawl into a live hedge that served as a fence for the garden; he was soon discovered. — "Let’s garrote this persecutor of the children of God," cried the assailants; and fearing for his life, the unfortunate abbot threw himself at the feet of their leader; vainly did he try to save him; several in his company reproached the abbot for all his violence, adding that it was time to atone for them. — "Hey! my friends," the poor abbot cried out to them, "if I am damned, do you want to do the same?" At these words, he was struck. — "This is for what you made my father suffer!" said one to him. — "This is for having condemned my brother to the galleys!" added another. It is said that he received one hundred and fifty-two wounds. He was expiring at the moment help arrived.

At this terrible account, anger and despair were painted on all faces. Everyone swore to avenge their persecuted brothers. They armed themselves and went to the entrance of the night at Pont-de-Montvert, in front of the castle: silence reigned there, the doors were barricaded: the abbot, who had heard of the conspiracy, had prepared to resist. He had with him a few soldiers and determined servants ready to sell their lives dearly. But the assailants broke down the doors and set fire to the castle. The roof was already in flames; the abbot tried to escape with a rope ladder through a window that opened onto the garden; but, slipping, he fell and broke his leg. Nevertheless, he managed to crawl into a live hedge that served as a fence for the garden; he was soon discovered. — "Let’s garrote this persecutor of the children of God," cried the assailants; and fearing for his life, the unfortunate abbot threw himself at the feet of their leader; vainly did he try to save him; several in his company reproached the abbot for all his violence, adding that it was time to atone for them. — "Hey! my friends," the poor abbot cried out to them, "if I am damned, do you want to do the same?" At these words, he was struck. — "This is for what you made my father suffer!" said one to him. — "This is for having condemned my brother to the galleys!" added another. It is said that he received one hundred and fifty-two wounds. He was expiring at the moment help arrived.

Such is the Protestant version of the death of Abbe du Chayla.

Here is now the Catholic account according to his biographer, M. Rescossier, dean of the chapter of Marvejols. "In the evening, there was a conference with the other missionaries, in which they spoke of the pains of purgatory; and in the end, they raised the question: if those who suffered martyrdom were subject to these pains.

Everyone having retired to their lodgings to sleep, he was warned that there were some strangers who were just beginning to arrive in the area. He thought it was a false alarm, until he heard a great tumult of people who had stormed his house and were firing their guns at the windows. Believing they were only demanding the release of a few prisoners taken from the assemblies of the fanatics, he ordered that they be let out. These wretched people no sooner saw the door open than they rushed into the house; they broke down a door to a low room where an altar had been set up to celebrate the holy mass, and, having made a bonfire in the middle of this chapel, they set it on fire to perish M. the abbot in the flames of this house. He tried to escape through the window using his bed sheets; but these ties being not long enough, he fell from quite a height. This fall shattered part of his body; he crawled into some brush, where he remained until he was discovered, thanks to the light cast by the fire of his house.

They rushed upon him; they dragged him through the street of this village (Le Pont-de-Montvert) that leads to the bridge. They read to him all imaginable insults, taking him by the nose, by the ears, and by the hair, throwing him to the ground with the utmost violence, and lifting him up at the same time, spewing a thousand atrocious insults against this holy priest, telling him that he was not as close to death as he thought, that he only had to deny his religion and begin preaching Calvinism to guarantee himself against peril. This proposition scandalized our holy abbot, who asked to say his last prayer. They granted him what he asked. Then, kneeling at the foot of the cross that stands on the bridge and raising his hands towards heaven, he committed his soul to God with extraordinary fervor. These impious ones, enraged to see him kneeling at the foot of this cross, could no longer restrain themselves. The one who commanded them gave the signal to fire a shot in the lower abdomen of our holy abbot. Then this crowd threw themselves upon him as if in competition, and each wanting the satisfaction of giving him the death blow, they riddled his whole body with stabs. Those who verified his wounds reported that he had twenty-four mortal wounds, and that the others were so numerous that they could not be counted.

They rushed upon him; they dragged him through the street of this village (Le Pont-de-Montvert) that leads to the bridge. They read to him all imaginable insults, taking him by the nose, by the ears, and by the hair, throwing him to the ground with the utmost violence, and lifting him up at the same time, spewing a thousand atrocious insults against this holy priest, telling him that he was not as close to death as he thought, that he only had to deny his religion and begin preaching Calvinism to guarantee himself against peril. This proposition scandalized our holy abbot, who asked to say his last prayer. They granted him what he asked. Then, kneeling at the foot of the cross that stands on the bridge and raising his hands towards heaven, he committed his soul to God with extraordinary fervor. These impious ones, enraged to see him kneeling at the foot of this cross, could no longer restrain themselves. The one who commanded them gave the signal to fire a shot in the lower abdomen of our holy abbot. Then this crowd threw themselves upon him as if in competition, and each wanting the satisfaction of giving him the death blow, they riddled his whole body with stabs. Those who verified his wounds reported that he had twenty-four mortal wounds, and that the others were so numerous that they could not be counted.

The Abbe du Chayla was buried in Saint-Germain-de-Calberte in the tomb he had prepared during his lifetime; and his procession was followed by the entire Catholic population of the neighboring parishes of Pont-de-Montvert.

One might say that he would have done better to content himself with the role of a missionary without adding that of an inspector; for there he had soured all minds by denouncing their preachers and those who attended their assemblies, or by having their children confined in seminaries and convents to be educated; but, says his biographer, can one deny that it is permitted for a priest to denounce those who are rebellious to the State and to religion? We believe that such a justification needs no commentary. Such was the prelude to the camisard uprising, one of the most remarkable events in the history of the 18th century. "Comparable at its beginning to a spark that a drop of water could have extinguished, it ignited," says a historian, "to the point of capturing the full attention of the court, which rightly feared that the blaze would become general."

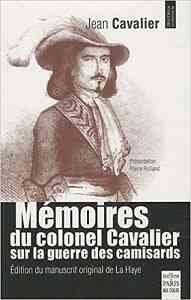

Then, indeed, the Cevennes mountaineers gathered and armed themselves for common defense. They chose for leaders the bravest among them: Roland, Cavalier, Ravenel, and Catinat. Roland established himself in the mountains, and Cavalier in the plain. Throughout the three years this war lasted, a handful of poorly armed, inexperienced men held their own against numerous and seasoned regular troops commanded by skilled generals: Montrevel, who complained of seeing his reputation compromised with "people in sack and rope," was replaced by Berwick and Villars. The latter, by opening roads through the Cevennes, shortened the duration of this war by facilitating troops' access to these mountains and rendering Protestant uprisings impossible. These roads were at the same time a blessing for the land and somewhat repaired the suffering that its inhabitants had endured for half a century; suffering whose memory brought tears to Bishop Flechier, and that would not have occurred had the priests of the Cevennes followed his wise counsel.

As for Jean Cavalier, the hero of the camisards, after making peace with Marshal Villars in 1704, he went to England, served there, and died as governor of Jersey.

As for Jean Cavalier, the hero of the camisards, after making peace with Marshal Villars in 1704, he went to England, served there, and died as governor of Jersey.

Before 1789, Gevaudan had its own states, which met alternately in Mende or Marvejols each year; they were presided over by the bishop of Mende, who attended assisted by his grand vicar; but this one had neither rank nor deliberative voice. Only in the absence of the bishop did he preside.

Fifty members, including the presiding bishop, composed the assembly; namely: seven from the clergy, twenty from the nobility, and twenty-two from the third estate. A canon, deputy from the chapter of Mende, Dom d'Aubrac, the prior of Sainte-Enimie, the prior of Langogne, the abbot of Chambons, the commander of Palhers, and the commander of Gap-Frances represented the clergy. Eight barons, who entered the states of the country annually and every eight years into the general states of Languedoc; namely: the barons of Tournels, Roure, Florac, Beges (formerly of Mercœur), Saint-Alban (formerly Conilhac), Apcher, Peyre, and Thoras (formerly Senarer); twelve gentlemen who were landowners, having the title of gentlemen; namely: Allenx, Montauroux, Dumont, Montrodat, Mirandal, Severac, Barre, Gabriac, Portes, Servieres, Arpajon, and La Garde-Guerin, whose possessor took in the assembly the quality of noble consul of La Garde Guerin; such were the representatives of the nobility.

Those from the third estate were: the three consuls of Mende, whether the states were held in Mende or in Marvejols; the three consuls of Marvejols, when the states were held in this city, and only the first consul when they gathered in Mende; a deputy from each of the sixteen towns or communities. As for the barons and gentlemen, they could be represented by envoys who did not need to prove their nobility; it was sufficient that they were from an honorable state, such as that of a lawyer or a doctor. Each year, the assembly instituted or confirmed the syndic and the clerk; these were the officers of the country. In Marvejols, a bailli and royal officers; in Mende, a bailli and officers appointed by the bishop alternately administered justice in the bailliage of Gevaudan. These two baillis were alternately ordinary commissioners in the assemblies of the country.

At the Revolution, Gevaudan formed the department of Lozere. Before this time, it was a sterile and poor land: the inhabitants left their mountains to cultivate the land in the southern provinces. They traveled in large bands to Spain, to the kingdom of Aragon. It is said that they brought back a lot of money; but while they exploited the laziness of the Spaniards by working for them, on the other hand, they were little valued by them, who regarded them as mercenaries and called them "gavachos," a term of contempt that they later extended to all Frenchmen. Some writers, great enthusiasts of etymology, even claim that it is from the ancient name of the Gabales that the Spaniards formed the word "gavacho," which they use as an insulting nickname.

At the Revolution, Gevaudan formed the department of Lozere. Before this time, it was a sterile and poor land: the inhabitants left their mountains to cultivate the land in the southern provinces. They traveled in large bands to Spain, to the kingdom of Aragon. It is said that they brought back a lot of money; but while they exploited the laziness of the Spaniards by working for them, on the other hand, they were little valued by them, who regarded them as mercenaries and called them "gavachos," a term of contempt that they later extended to all Frenchmen. Some writers, great enthusiasts of etymology, even claim that it is from the ancient name of the Gabales that the Spaniards formed the word "gavacho," which they use as an insulting nickname.

Later, however, the mountaineers of the Cevennes found resources against poverty in industry. They no longer emigrated and began to weave cadis and serges, whose renown spread even to foreign lands. "There is hardly a peasant who does not have a trade at home on which he works in the season when he does not cultivate the land, and especially during the winter, which is very long in these mountains for six whole months. Even children spin wool from the age of four." So expressed a traveler in 1760. Such is still today this land. Living in the midst of harsh mountains, in a poor and arid region, exposed to the onslaughts of a harsh climate, the farmers of Lozere, says M. Dubois, necessarily have rustic manners, rough and coarse habits. Nevertheless, their character is good and simple. They are naturally gentle and even affable towards strangers, peacefully submissive to the authorities they respect, filled with reverence and devotion for their parents whom they love.

Their life is laborious and difficult. Most have to struggle against the natural sterility of the surrounding land. Their food is simple and frugal: it consists of dairy products, butter, cheese, lard, salted beef, dried vegetables, and rye bread. They add potatoes or chestnuts. Their usual drink is spring water; but they are accused of liking wine and of giving in to drunkenness when fairs or other occasions lead them to villages where there are taverns. Their homes, generally low and damp, are uncomfortable and unhealthy. The manure pits that surround them spread putrid miasmas around.

Their life is laborious and difficult. Most have to struggle against the natural sterility of the surrounding land. Their food is simple and frugal: it consists of dairy products, butter, cheese, lard, salted beef, dried vegetables, and rye bread. They add potatoes or chestnuts. Their usual drink is spring water; but they are accused of liking wine and of giving in to drunkenness when fairs or other occasions lead them to villages where there are taverns. Their homes, generally low and damp, are uncomfortable and unhealthy. The manure pits that surround them spread putrid miasmas around.

Farmers are very attached to their religion and love religious ceremonies: all, Catholics and Protestants, have equal respect for the ministers of their cult. They also stubbornly maintain their old habits, hold on to their prejudices, to their agricultural routine, to the coarse clothing they have worn since childhood. They are not eager to change, even when their interests should benefit from the change. Their slowness, apathy, and indifference are sufficient to thwart all improvement projects. The young people have a great attachment to their village: they reluctantly submit to the law that forces them into military service, and the department is one of those where the most deferrals are counted; nevertheless, when they have joined their battalion, they prove to be intrepid and disciplined soldiers.

They are very fit for the fatigues of war, being of strong constitution and robust temperament. The inhabitants of the cities naturally have more amiability in character than those of the countryside; like them, they are frugal and laborious and yet hospitable and charitable. The people of Lozere generally possess intelligence, natural spirit, and sound judgment. If they seem to cultivate letters and the arts less, at least they succeed better in the study of the natural sciences and mathematics. Victor Adolphe Malte-Brun, work from 1882

Former holiday hotel with a garden along the Allier, L'Etoile Guest House is located in La Bastide-Puylaurent between Lozere, Ardeche, and the Cevennes in the mountains of Southern France. At the crossroads of GR®7, GR®70 Stevenson Path, GR®72, GR®700 Regordane Way, GR®470 Allier River springs and gorges, GRP® Cevenol, Ardechoise Mountains, Margeride. Numerous loop trails for hiking and one-day biking excursions. Ideal for a relaxing and hiking getaway.

Copyright©etoile.fr