Exploitation of the Villefort mines |

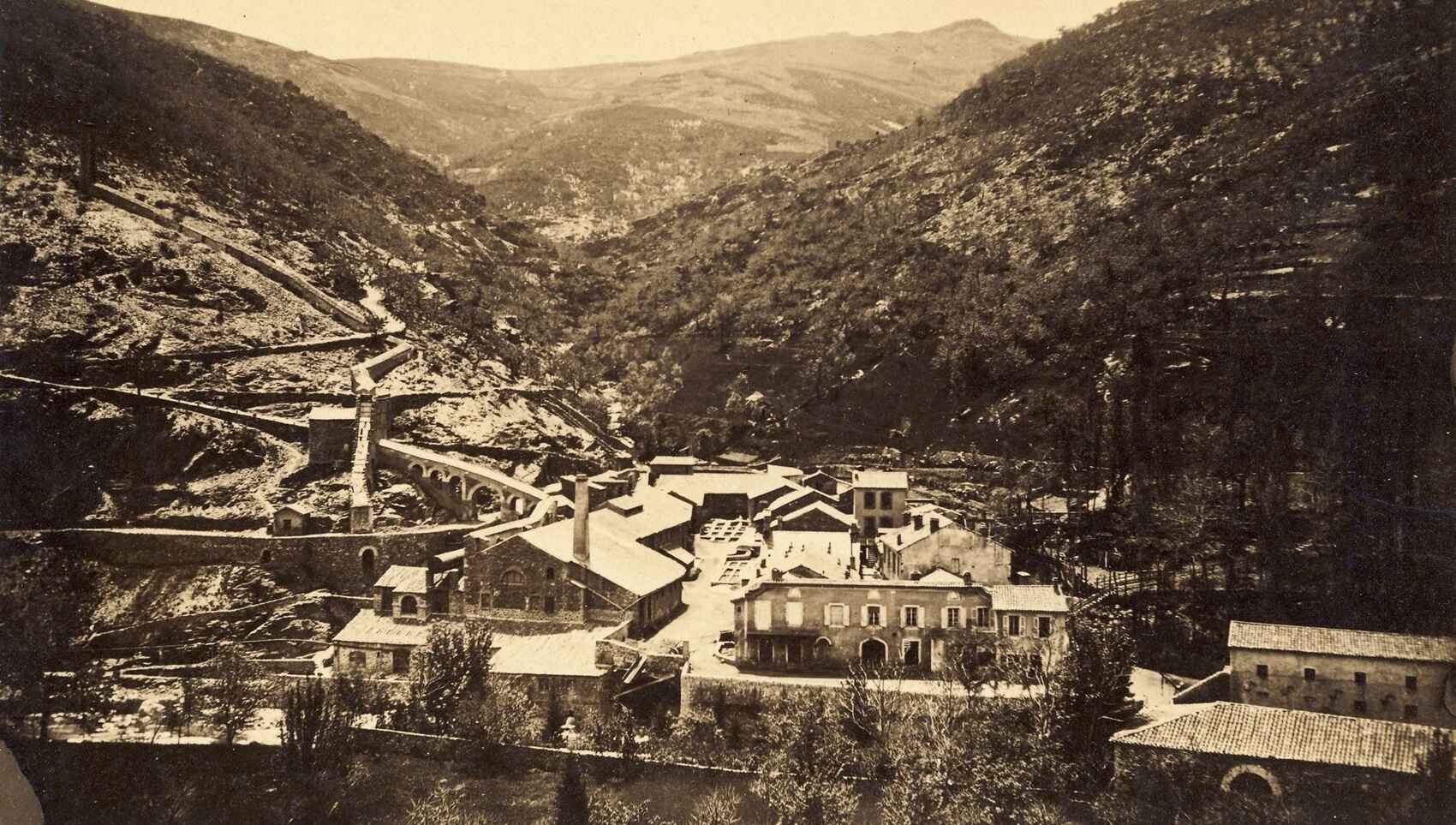

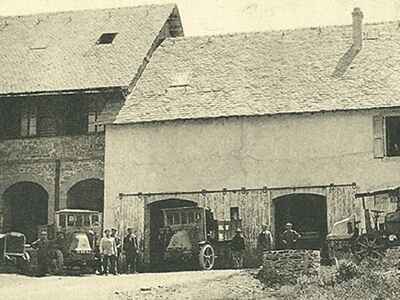

Mining in Villefort represents a fascinating chapter in the industrial history of the Lozère region, dating back to Roman times. The silver-bearing lead deposits of Vialas and Villefort experienced their true boom in the Middle Ages, driven by local lords. In the nineteenth century, activity intensified with the opening of deep galleries to extract the precious ore used throughout the region. Miners primarily extracted argentiferous galena, a mixture of lead and silver whose purity was highly prized at the time. The surrounding landscape still bears the marks of this era, with forgotten mine entrances and remnants of spoil heaps. The village's social life was structured around this arduous industry, which attracted a hardworking workforce from the nearby mountains. The arrival of the railway accelerated exports to foundries before global competition led to a decline in the industry.

In the heart of the mountains of Villefort, the veins of the earth contained hidden treasures, coveted by those who dared to plunge into its depths. On this day, June 1, 1640, Firmin Mazelet, a man of vision and ambition, received royal permission to explore the innards of the earth. He was granted the right to search for and extract gold, silver, copper, tin, lead, and any other precious metal in the vast provinces of Languedoc and Rouergue for a duration of six years.

In the heart of the mountains of Villefort, the veins of the earth contained hidden treasures, coveted by those who dared to plunge into its depths. On this day, June 1, 1640, Firmin Mazelet, a man of vision and ambition, received royal permission to explore the innards of the earth. He was granted the right to search for and extract gold, silver, copper, tin, lead, and any other precious metal in the vast provinces of Languedoc and Rouergue for a duration of six years.

The following year, documents confirmed that Mr. Firmin Mazelet de Savage was busy in the mines of the parish of Villefort. The archives of 1642 confirmed the existence of these operations, but, like a fleeting breath, they suddenly ceased in 1643.

Time passed, and in 1649, the Marquis de la Charce, attracted by the call of underground riches, also obtained permission to open mines in Languedoc and Provence. But the years went by without any news of work in the territory of Villefort.

Time passed, and in 1649, the Marquis de la Charce, attracted by the call of underground riches, also obtained permission to open mines in Languedoc and Provence. But the years went by without any news of work in the territory of Villefort.

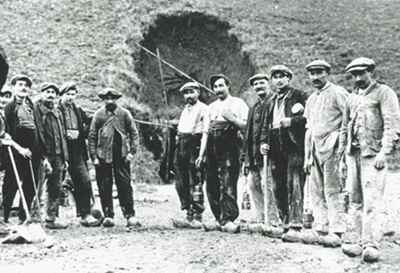

Then, in 1733, an Irishman named Brown arrived with a new authorization, rekindling hopes of wealth. He opened lead mines near Villefort and Alès and, with unwavering determination, brought experienced miners, washers, smelters, and refiners from Germany and England, ready to reveal the secrets of the earth.

However, between 1734 and 1741, a dispute broke out between Brown and a man named Bonnet, who claimed to have discovered mines in various locations from which he had extracted wealth in 1734 and 1736. A lengthy trial ensued, and eventually, the concession was withdrawn from Brown in 1756.

Finally, a letter dated 1764 mentioned that the lead mines of Peyrelade, Villefort, and others like them, nestled in the Cévennes, had been granted to a certain Ménard. However, he, perhaps discouraged by the challenges or whims of the earth, immediately abandoned them, leaving the treasures of Villefort sleeping beneath the mountains, waiting for other adventurers to come and awaken them.

On June 15, 1769, a wind of change blew over the mines of Villefort. An exploitation permit was granted to a company under the direction of Marquis de Luchet, Pierre-Louis, with Maulevrier as a partner in this enterprise. The mines, which had been the site of incessant activities, were then under the scrutinizing gaze of Jars, who, on August 27, 1771, prepared a detailed report on the state of the works.

On June 15, 1769, a wind of change blew over the mines of Villefort. An exploitation permit was granted to a company under the direction of Marquis de Luchet, Pierre-Louis, with Maulevrier as a partner in this enterprise. The mines, which had been the site of incessant activities, were then under the scrutinizing gaze of Jars, who, on August 27, 1771, prepared a detailed report on the state of the works.

Four veins pulsed at the heart of the mountain: Lagarde, whose promises of wealth were dwindling under the current management; Bayard, an old vein that had seen better days; Pierrelade, where the bustle of work could not dispel doubts about its profitability; and Masimbert, a virgin vein that the ancients may have spared, perhaps out of respect or fear.

In 1776, the concession of Villefort and Vialas was established for thirty years, passing into the hands of Antoine de Gensanne. This man, driven by a passion for the depths, embarked on the rehabilitation of the mines of Peyrelade, Fressinet, and Mazimbert. However, the galena deposits proved to be recalcitrant, and Gensanne had to extend his search to other locations in the concession, such as Bayard, la Garde, Valcrouses, la Devèze, Charnier, la Rouvière, and many others.

In 1776, the concession of Villefort and Vialas was established for thirty years, passing into the hands of Antoine de Gensanne. This man, driven by a passion for the depths, embarked on the rehabilitation of the mines of Peyrelade, Fressinet, and Mazimbert. However, the galena deposits proved to be recalcitrant, and Gensanne had to extend his search to other locations in the concession, such as Bayard, la Garde, Valcrouses, la Devèze, Charnier, la Rouvière, and many others.

In his work from 1778, Gensanne paints a vivid picture of the mine: the miners, strangers to the region, shaping the rock with their powder, while laborers, young men from the area, busily worked around them. Years passed, and in 1781, efforts focused on the veins of Villaret and Malfrèzes, leaving behind Mazimbert and Peyrelade. The copper mine at Fressinet experienced resounding success until 1781. The company at Villefort, for its part, still seemed to be active in 1790, but six years later, the mines were abandoned, their insides silent.

Marrot, in 1824, mentioned a resumption of activities, although the visit reports from 1821 to 1825 remain silent on the subject. It was only after several modifications of the concession that work timidly resumed in 1821, with modest research on the veins of Peyrelade and Mazimbert. Finally, in 1872, following the merger of several concessions, a new impetus was given to research at Peyrelade, reviving hope for a land rich in buried promises.

Marrot, in 1824, mentioned a resumption of activities, although the visit reports from 1821 to 1825 remain silent on the subject. It was only after several modifications of the concession that work timidly resumed in 1821, with modest research on the veins of Peyrelade and Mazimbert. Finally, in 1872, following the merger of several concessions, a new impetus was given to research at Peyrelade, reviving hope for a land rich in buried promises.

The fate of the mines of Villefort took a new turn on August 7, 1883, when the Company of the Mines of Magnetic Iron Ore of Mokta-el-Hadid took over the reins of the operation. Years passed, and the Vialas deposit, exhausted, led to a significant reduction of the concession area on October 13, 1909, setting the boundaries of the current concession of Villefort at 3563 hectares. The unceasing quest for underground riches continued, but in 1919, Mokta-el-Hadid, tired of the challenges posed by the earth, relinquished its mining title to a certain Mr. Joosten. The flame of exploration still burned between June 1930 and early 1931, with the final efforts made in the Chambon district and in Mazimbert. But like all epic tales, that of Villefort saw a parade of concessionaires, each looking to uncover the buried mysteries. Recylex SA, the last of these holders, inherited a story rich in twists and turns, marked by human ambition and the indomitable breath of nature.

The Life of the Miners of Lozère

The Life of the Miners of Lozère

The search for gold has always been a powerful driving force. Although the gold mines in Lozère were fewer than those for other metals, they generated great interest. Miners searching for gold nuggets descended into dark galleries, armed with shovels and picks, hoping to unearth riches. Silver, on the other hand, was often extracted in association with other metals.

Silver veins attracted miners due to their high market value. Copper, tin, and lead, while less prestigious, also played an essential role in the local economy. The miners of Lozère had to adapt and juggle the extraction of several metals according to market fluctuations. The daily life of the miners was marked by grueling work hours. Rising before dawn, walking to the mine, and spending long days digging in the dark was the norm.

Miners often found themselves in groups, forming bonds of friendship and solidarity amid harsh working conditions. Breaks were precious, allowing miners to share stories and support one another. The families of miners often lived in villages close to the mines, where life was marked by community and traditions. Women and children played a crucial role in supporting families, taking care of household tasks, and helping with the domestic economy. Life was simple, but resources were limited, and economic difficulties were frequent.

The life of the miners was not solely marked by work. The battles for better working conditions were an essential part of their existence. Miners often organized into unions to demand rights, fair wages, and safety conditions. Strikes and demonstrations were forms of expression to make their voices heard against mine owners, who often neglected the safety and well-being of their workers. Despite their efforts, many miners suffered from work-related illnesses such as silicosis, and accidents were common. The constant risk of losing a loved one in the dark galleries weighed heavily on families.

Former holiday hotel with a garden along the Allier, L'Etoile Guest House is located in La Bastide-Puylaurent between Lozere, Ardeche, and the Cevennes in the mountains of Southern France. At the crossroads of GR®7, GR®70 Stevenson Path, GR®72, GR®700 Regordane Way, GR®470 Allier River springs and gorges, GRP® Cevenol, Ardechoise Mountains, Margeride. Numerous loop trails for hiking and one-day biking excursions. Ideal for a relaxing and hiking getaway.

Copyright©etoile.fr