The Castle of Chambonas |

The Castle of Chambonas |

The Château de Chambonas was probably founded in its current state by Henri de la Garde, who lived at the beginning of the 17th century. It would therefore belong to the wave of construction that affected the country after the first religious wars, like Joviac and many others. Henri de la Garde acquired various lordships from the family of Borne. He was also a fierce opponent of the Huguenots during the wars of the reign of Louis XIII. The soldier from Vivarais recounts in his Commentaries that the city of Vans had followed the rebellion of Privas, which forced Mr. de Chambonas to strengthen his castle located about a half-league away, notably with a strong garrison that he maintained there. Although four or five hundred men of war usually emerged from Vans, both from the inhabitants and from some companies they maintained there, they were so well contained by Mr. de Chambonas that they had enough to occupy themselves without seeking elsewhere... He took their Chabiscol, a fortified house for the convenience of their mill, which greatly inconvenienced them: he killed a large number of their best soldiers, and every season caused them great damage to their vineyards.

The Château de Chambonas was probably founded in its current state by Henri de la Garde, who lived at the beginning of the 17th century. It would therefore belong to the wave of construction that affected the country after the first religious wars, like Joviac and many others. Henri de la Garde acquired various lordships from the family of Borne. He was also a fierce opponent of the Huguenots during the wars of the reign of Louis XIII. The soldier from Vivarais recounts in his Commentaries that the city of Vans had followed the rebellion of Privas, which forced Mr. de Chambonas to strengthen his castle located about a half-league away, notably with a strong garrison that he maintained there. Although four or five hundred men of war usually emerged from Vans, both from the inhabitants and from some companies they maintained there, they were so well contained by Mr. de Chambonas that they had enough to occupy themselves without seeking elsewhere... He took their Chabiscol, a fortified house for the convenience of their mill, which greatly inconvenienced them: he killed a large number of their best soldiers, and every season caused them great damage to their vineyards.

In September, he invited Mr. de Vernon to assist him with the grape harvest; on their side, they prepared for it as well, and in the end, there were such good skirmishes that several on both sides were harvested themselves... In 1628, he was again found alongside Guillaume de Balazuc in the war against the Duke of Rohan. It was in 1630 that the bridge of Chambonas was put back into service. According to Jacques Schnetzler, it has always withstood since then.

In September, he invited Mr. de Vernon to assist him with the grape harvest; on their side, they prepared for it as well, and in the end, there were such good skirmishes that several on both sides were harvested themselves... In 1628, he was again found alongside Guillaume de Balazuc in the war against the Duke of Rohan. It was in 1630 that the bridge of Chambonas was put back into service. According to Jacques Schnetzler, it has always withstood since then.

Antoine de la Garde, the son of Henri, managed to acquire the lordship of Chambonas, still from the family of Borne. He also purchased among others, the lordship of Sablières on March 4, 1638, from Jacques du Roure, who himself held it from the lord of Sablières, Jean de Bourguinhon. It cost him 1,156 livres and 19 sols, and included 40 tenants, who paid him with oats, rye, wine, fresh chestnuts, bread, hens, beeswax, and a little money.

Louis-François, son of Antoine, married Charlotte de la Baume de Suze on August 19, 1629, the sister of the Bishop of Viviers. They had two sons, of whom the elder, another Louis-François, took the title of Marquis in 1683 thanks to letters patent from Louis XIV, and the other, Charles-Antoine, born in 1735, was for a long time a vicar of his uncle Monseigneur de Suze, then Bishop of Lodève, coadjutor, and later Bishop of Viviers (1600-1713). The family had already become one of the principal ones in the country.

The peak of the Chambonas family. It was as coadjutor that Charles-Antoine de Chambonas wrote in 1684 in favor of the Huguenot inhabitants of Privas, requesting the king "to allow them to recover from the pitiful state to which they have been reduced, mainly to be able to employ their goods and lives for His Majesty." At this time of persecution, when the Privadois had been expelled for the second time from their city in 1664, this attitude from a member of the high clergy is worth highlighting. It is said that at the time of the "little prophets," he went from parish to parish, obtaining the grace of many peasants. Damville said of him that "this prelate, before these disorders, had worked effectively for the religion in this country, taking the place of the old bishop, his uncle, who due to his advanced age, was unable to act."

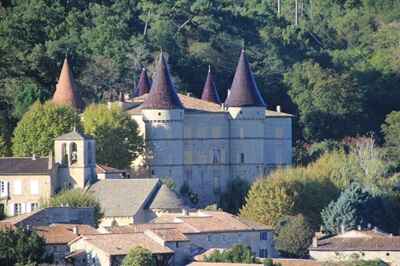

Louis-François, the first Marquis of Chambonas, wrote in 1672: "I have my castle with four towers, enclosed by walls, barns, a courtyard, stables, and a dovecote," which suggests that the castle had its current appearance, for the most part, from that time. Louis-François died without descendants in 1710. Another of his brothers, Henri-Joseph, succeeded him. Henri-Joseph had married Charlotte de Fontanges in 1685, a lady-in-waiting to the Duchess of Maine. She was involved at one point in the Cellamare conspiracy in December 1718, and the Marquise de Chambonas requested the honor of sharing a few days of her imprisonment.

Louis-François, the first Marquis of Chambonas, wrote in 1672: "I have my castle with four towers, enclosed by walls, barns, a courtyard, stables, and a dovecote," which suggests that the castle had its current appearance, for the most part, from that time. Louis-François died without descendants in 1710. Another of his brothers, Henri-Joseph, succeeded him. Henri-Joseph had married Charlotte de Fontanges in 1685, a lady-in-waiting to the Duchess of Maine. She was involved at one point in the Cellamare conspiracy in December 1718, and the Marquise de Chambonas requested the honor of sharing a few days of her imprisonment.

It was undoubtedly Henri-Joseph who had the famous gardens of Chambonas realized between 1710 and 1729. It is certain that Le Nôtre, the famous gardener of Louis XIV, did not direct their completion as he died in 1700. However, Abbé Charay, while classifying the works of the library, found a Theory and Practice of Gardening attributed to Leblond, a student of Le Nôtre, who, according to an anonymous note, would have drawn the gardens of Versailles, the Tuileries, and Chambonas. The realization may have come much later than the drawing; "Nothing is certain, but everything is plausible," prudently concluded the learned abbé.

It was undoubtedly Henri-Joseph who had the famous gardens of Chambonas realized between 1710 and 1729. It is certain that Le Nôtre, the famous gardener of Louis XIV, did not direct their completion as he died in 1700. However, Abbé Charay, while classifying the works of the library, found a Theory and Practice of Gardening attributed to Leblond, a student of Le Nôtre, who, according to an anonymous note, would have drawn the gardens of Versailles, the Tuileries, and Chambonas. The realization may have come much later than the drawing; "Nothing is certain, but everything is plausible," prudently concluded the learned abbé.

Henri-Joseph died in 1729, and his successor was his son Scipion-Louis-Joseph, who first married Claire-Marie, Princess of Ligne, on March 19, 1722, then became a widower, married Marie de Grimoard de Beauvoir du Roure, from the powerful Roure family, who had acquired the lordship of Vans in the 17th century. Scipion-Louis-Joseph de Chambonas was primarily a military man, who left his career in 1746 because he had not succeeded in obtaining the staff of Marshal of France. Albin Mazon attributes to him the paternity of the famous gardens, between 1737 and 1742.

He died in 1765, leaving a young son from his second marriage, Victor-Louis-Scipion, who was the last Marquis of Chambonas. According to Mazon, this young man married a natural daughter of the Minister of War, the Marquis de Saint-Florentin. He separated from her dramatically, and the trial fueled the chronicles of the time. Although she was as beautiful as an angel, Merle de Lagorce, in his Memoirs of a Courtier, which Mazon cites, says that he hardly took care of her, preferring to have her painted as a monkey, a bear, a hermit, a beggar, an abbé, a nun, a peasant, etc., on the panels of his salon. He himself enjoyed dressing up as a Franciscan; he had founded with his friend the Duke of Bouillon an order of Felicity. Both alternated as grand masters, and the admitted persons wore a green ribbon on their hearts, a symbol of hope. The statutes contained the maxims of the most refined gallantry, says Merle de Lagorce. This discretion probably deprives us of juicy details, but the memorialist explains that his castle was never lacking in strangers; it was rather their residence than his. After the revolt of the Armed Masks (1783), the four advisors sent on site by the Parliament of Toulouse were housed at the Château de Chambonas.

The Marquis de Chambonas enthusiastically accepted the ideas of the Revolution, following La Fayette. He became a camp marshal in the Seine troops in April 1792, then, after the resignation of the Girondin ministry on June 13, Minister of Foreign Affairs of Louis XVI, pushed by Duport, one of the leaders of the Feuillant party. His ministry lasted barely a month, from June to July 1792; he sought, as much as possible, to break the alliance between Vienna and Berlin, and especially to suspend hostilities. The Girondin leader Brissot accused him of treason on July 8, for not having reported the advance of the Prussians. He was also accused of having trafficked arms with Beaumarchais. He calmly replied that he was not informed, and it was only a few days later that the Legislative Assembly proclaimed the Fatherland in danger. He handled current affairs until July 23, then discreetly slipped away to England.

The Marquis de Chambonas enthusiastically accepted the ideas of the Revolution, following La Fayette. He became a camp marshal in the Seine troops in April 1792, then, after the resignation of the Girondin ministry on June 13, Minister of Foreign Affairs of Louis XVI, pushed by Duport, one of the leaders of the Feuillant party. His ministry lasted barely a month, from June to July 1792; he sought, as much as possible, to break the alliance between Vienna and Berlin, and especially to suspend hostilities. The Girondin leader Brissot accused him of treason on July 8, for not having reported the advance of the Prussians. He was also accused of having trafficked arms with Beaumarchais. He calmly replied that he was not informed, and it was only a few days later that the Legislative Assembly proclaimed the Fatherland in danger. He handled current affairs until July 23, then discreetly slipped away to England.

He found security there, but not fortune, as he borrowed as much as he could, until being brought before the English courts in 1805. He was sentenced to a heavy fine and imprisonment. He was struck off the list of émigrés as early as 26 Thermidor Year III, but it seems he did not return to France. It is believed that he died in poverty in London in 1807, and his son Alphonse de la Garde, principal controller of the United Rights in Ambert, in Puy-de-Dôme, hurried to sell the castle on February 13, 1808, to Charles-François de Chanaleilles, a former knight of the Order of Malta, general director of the Domains in Martinique, before Mr. Postelle, a notary in Paris.

"The château is undoubtedly the most happily and grandly situated seigneurial residence we have in our ancient province. It juts out prominently on the foreground of a painting, of which the cheerful territories that envelop and encircle the village of Chambonas form the border. Remove the houses that press and constrict it at one point, scatter the air and space around it, give its lovely landscaped garden the grand proportions of one of those immense parks provided for the lords of the English aristocracy, and you will have one of those privileged homes to which nature and the hand of man have nothing more to add."

"The château is undoubtedly the most happily and grandly situated seigneurial residence we have in our ancient province. It juts out prominently on the foreground of a painting, of which the cheerful territories that envelop and encircle the village of Chambonas form the border. Remove the houses that press and constrict it at one point, scatter the air and space around it, give its lovely landscaped garden the grand proportions of one of those immense parks provided for the lords of the English aristocracy, and you will have one of those privileged homes to which nature and the hand of man have nothing more to add."

Ovide de Valgorge wrote this in 1846, and it must be acknowledged that a century and a half later, there is not much to add, except that the English gardens have nothing to do with those of Chambonas... On a plan preserved at the château, dating probably from 1808, the date of the purchase by Charles de Chanaleilles, one can see regularly planted terraces of trees, probably mulberries, and triangular lawns of which some still persist today. The château and the park were built in line with the bridge, thus giving a magnificent perspective, but the monumental gate near the Chassezac is never used.

We now enter the estate from the east, and we immediately see the powerful sandstone escarpment on which the castle was built. To the northeast, an annex building, as tall as the castle, likely dates from the 18th century, and connects to the main building via a spiral staircase. The northwest corner of the castle dates back to the Middle Ages, but the rest of the building probably mainly originates from the 17th century.

We reach the upper terrace by a double-revolution staircase surrounding a basin. It is shaded by four venerable plane trees, whose powerful roots protrude here and there on the ground. Large glazed vases, works of potters from Anduze from the early 19th century, are still present on the left. In front of us, we discover the monumental fountain, whose water then flows through a whole play of basins and pools, across the garden. Above the fountain, a funerary cippus still dominates what must have been an ancient basin. It seems that many cippi were once found around Chambonas and that they have disappeared, a loss due either to negligence or to greed. The archaeological map of Gaul makes no mention of them.

The main façade faces south, towards the garden and the fountains. It is flanked by two round towers, two stories high, separated by cornices, just like it. The western tower is topped with brown tiles, while the eastern one is covered with slates like the other three. Above the gate, there are watchtowers framing a clock, resting on beautiful corbels. This is undoubtedly an addition from the 19th century. The monumental gateway, framed by a triple bossage and topped by a basket-handle arch bearing the coat of arms of the Chanaleilles, is one of the most remarkable in the region. The resemblance to the door in the southwest of the Château d'Aubenas is evident. Two recent wrought-iron torches, though of very good taste, complete the ensemble.

The main façade faces south, towards the garden and the fountains. It is flanked by two round towers, two stories high, separated by cornices, just like it. The western tower is topped with brown tiles, while the eastern one is covered with slates like the other three. Above the gate, there are watchtowers framing a clock, resting on beautiful corbels. This is undoubtedly an addition from the 19th century. The monumental gateway, framed by a triple bossage and topped by a basket-handle arch bearing the coat of arms of the Chanaleilles, is one of the most remarkable in the region. The resemblance to the door in the southwest of the Château d'Aubenas is evident. Two recent wrought-iron torches, though of very good taste, complete the ensemble.

We then enter a vast vestibule located on the site of an old inner courtyard, in which rises a magnificent monumental staircase, with robust balusters, probably the finest left to us by the 17th century. The furnishings have changed significantly since the visit that Abbé Charay made and described in 1966: there are still two suits of armor, at least one of which seems to be from that era. The tapestries have disappeared, but the magnificent Venetian lantern that lights the space remains. A statue of Étienne Marcel, undatable, watches the visitor with an enigmatic air.

On the left, there is the guard room, vaulted with ribbed arches, furnished in the 16th century, and which is an ancient tinel, or dining room. One particularly notices a very beautiful fireplace with a basket-handle arch, flanked by two alcoves; in the left one, you can see a warming cupboard for dishes, closed by a stone door. The fireplace plaque bears two bombards, which apparently evokes the honorary function of camp master of Marquis Scipion de la Garde, who occupied the castle in the mid-18th century.

On the right, we enter an Italian-style salon, covered with ribbed vaulted ceilings. The wall decor has been painted in distemper, as in the grand salon of the diocese of Viviers. Knowing that a member of the Chambonas family was bishop of Viviers a few decades before the construction of the episcopal palace, and that this was partly financed by money from the Chambonas, one can obviously think that the artists belonged to the same group. Each wall is dedicated to one of the four elements: fire, symbolized by a salamander and a pot of fire, is represented near the fireplace; earth, featuring an elephant, a dromedary, a horse, and a lion, is on the right. Air, opposite, is depicted with its birds, and water is finally symbolized, on the left, by fountains, shells, and Neptune's trident. The ceiling features Music, the Arts and Sciences, Hunting and Agriculture, all in a lush and colorful floral decor. The Louis XV furniture seen by Abbé Charay has sadly disappeared.

On the right, we enter an Italian-style salon, covered with ribbed vaulted ceilings. The wall decor has been painted in distemper, as in the grand salon of the diocese of Viviers. Knowing that a member of the Chambonas family was bishop of Viviers a few decades before the construction of the episcopal palace, and that this was partly financed by money from the Chambonas, one can obviously think that the artists belonged to the same group. Each wall is dedicated to one of the four elements: fire, symbolized by a salamander and a pot of fire, is represented near the fireplace; earth, featuring an elephant, a dromedary, a horse, and a lion, is on the right. Air, opposite, is depicted with its birds, and water is finally symbolized, on the left, by fountains, shells, and Neptune's trident. The ceiling features Music, the Arts and Sciences, Hunting and Agriculture, all in a lush and colorful floral decor. The Louis XV furniture seen by Abbé Charay has sadly disappeared.

At the base of the southeast tower is a small chapel, also vaulted, painted blue with gold stars in the style of the 19th century. The altar seems older, perhaps from the 17th century; opposite, there are the arms of Chanaleilles (again) and especially, below, a magnificent relief portrait of Christ. Abbé Charay attributed this work to the famous goldsmith and sculptor of the Renaissance, Benvenuto Cellini (1500-1571). Of course, caution is advised: however, even if it is only a copy, the finesse of the features, the nobility and gentleness of the face undeniably deserve the most active attention.

The next room, set up as a billiard room, also vaulted with ribbed arches, communicates with the Italian salon through a magnificent 17th-century portal, and a whole floral decoration of the Louis XV period. The base of the northeast tower is furnished as a lounge, in the same style. The glazed tile flooring of these two rooms, dating from the 17th century, is a pure splendor. Further on, there is another room, covered with coffered beams, where one can admire for a moment a superb faience stove and a mirror frame whose elegance and grace evoke the entire Enlightenment civilization.

The next room, set up as a billiard room, also vaulted with ribbed arches, communicates with the Italian salon through a magnificent 17th-century portal, and a whole floral decoration of the Louis XV period. The base of the northeast tower is furnished as a lounge, in the same style. The glazed tile flooring of these two rooms, dating from the 17th century, is a pure splendor. Further on, there is another room, covered with coffered beams, where one can admire for a moment a superb faience stove and a mirror frame whose elegance and grace evoke the entire Enlightenment civilization.

The paintings described by Abbé Charay in 1966 have disappeared. The upper floors are currently occupied by apartments; we were unable to see the "red room," or "bishop's room," that he mentions, nor the "Italian factories" painted on canvas and framed with rocaille and polychrome flowers. The numerous paintings he described have probably vanished. As for the archives, they are now located at the Departmental Archives of Privas.

It is good to know that the façades and roofs of the Château de Chambonas have been listed in the Supplementary Inventory of Historical Monuments since the decree of April 2, 1963. The entire park, the grand staircase, the Italian salon, the grand salon that follows it, as well as the small salon of the northeast tower, are classified historical monuments.

The Château de Chambonas is strictly private property. However, on certain occasions, the public can access the gardens. Local scholarly societies are sometimes received in the rooms we have described. In any case, it is of course essential to respect the privacy of the inhabitants. Ardèche, land of castles. By Michel Riou. Published by La Fontaine de Siloe.

Former holiday hotel with a garden along the Allier, L'Etoile Guest House is located in La Bastide-Puylaurent between Lozere, Ardeche, and the Cevennes in the mountains of Southern France. At the crossroads of GR®7, GR®70 Stevenson Path, GR®72, GR®700 Regordane Way, GR®470 Allier River springs and gorges, GRP® Cevenol, Ardechoise Mountains, Margeride. Numerous loop trails for hiking and one-day biking excursions. Ideal for a relaxing and hiking getaway.

Copyright©etoile.fr